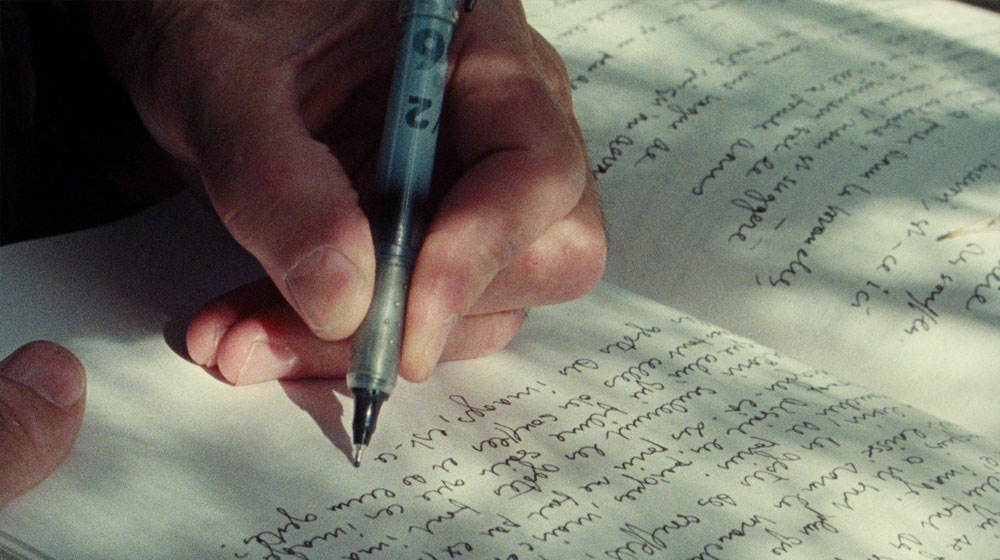

Angela Ricci kept a diary which she filled with drawings and descriptive notes: meetings, travelogues, things she’d read, reflections on her creative process. When she died in February 2018, her life and work partner, Yervant Gianikian, decided to film these. “Angela comes back to life for me in her handwritten words, in the light calligraphy that accompanies her drawings and watercolours. I look at our forgotten films, the private recordings that lie behind our work of reinterpreting and resignifying the film archive (…). These are my memories with Angela and our life together. I reread these notebooks and discover others I knew nothing about. New things emerge from her last notes and drawings”.

I diari di Angela is a different form of diary; a cinematographic format that, instead of following the thread of the present, as Angela did day by day, jumps around and combines moments that are far apart in time, gradually creating a single bundle. The project consists of two chapters, completed in 2018 and 2019, that shift between cinema, photography, painting and literature while Gianikian turns the pages of her diary by hand. It’s a story of more than forty years as a couple and of obsessive, meticulous work, committed to preserving the visibility of the nitrate images before the film decays, both physically and chemically, or disappears (as seen in that wonderful kernel of their filmmaking that’s the short film Trasparenze). The movement of this gesture, of working with four hands, has repercussions and makes this loving elegy even more moving, as if it were a last hand outstretched.

From the search, in a Russian archive, for 35mm film of the prisoners of war in the Austro-Hungarian Empire to trips to screen their films in the United States in 1981; from the tumultuous collision of idolatries in Jerusalem to the wonderful evocation, using Angela’s drawings and texts, of her memories of the Second World War. “The promise made to Angela is renewed and shines again through the passionate writing in her pages, which pass through the narrow, dark eye of the violent world without impediment” (Gianikian).

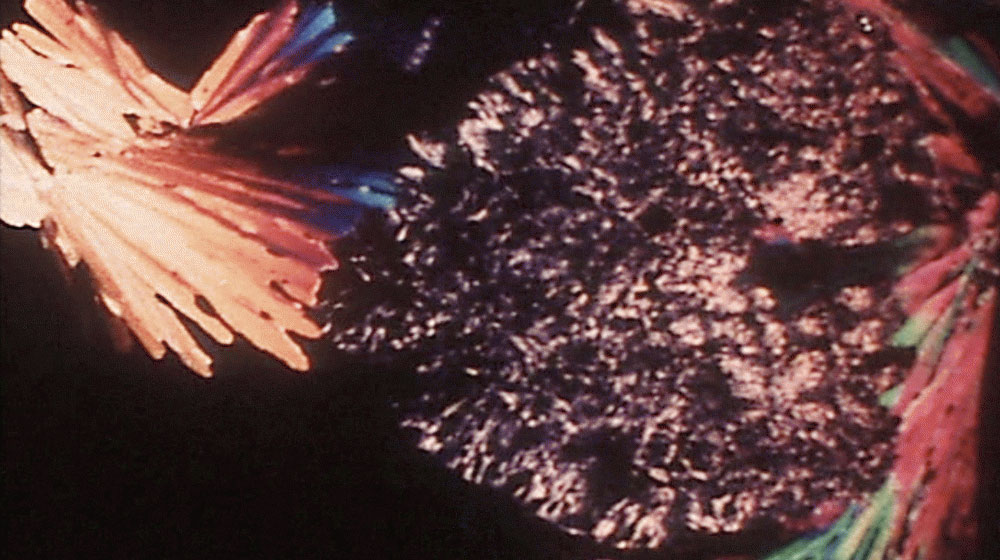

Since 1975 these two filmmakers, famous for their pioneering archive films as a form of resistance against historical amnesia, decided to show “the contemporary nature of the past, the continuing presence of the past”; to show how, when seen today, archive images can reveal new thoughts and associations through the dialectic between past and present. Neither archivists in the strict sense of the word nor documentalists, their work activated how we see things, getting closer to the details of single frames to uncover them and see what had not been seen or see it differently. “We did it using a process we called an ‘analytical camera’, a cinematographic device we built that enabled us to reproduce what we’d seen during the manual process. In this material we noticed how soldiers fell when they were shot in battle, falling at an infinitesimal speed, in just two or three frames. This movement isn’t seen in either the cinema or television because of the incredibly fast speed, almost subliminal, and we set out to show exactly what we’d seen in the manual process, which in this case was the death of a soldier”.

Here, however, the film deals with the death of one part of that way of seeing things; the death of Angela. What kind of analysis or approach is suitable now, what kind of speed can be perceived? I diari di Angela contains some fragments of her work but, above all, it contains other kinds of personal images, in Super 8, video or photographs; sometimes as raw blocks of experience, other times as albums. These are no longer the visual fragments or corpses of history but rather pieces of history in miniature, of her own history.

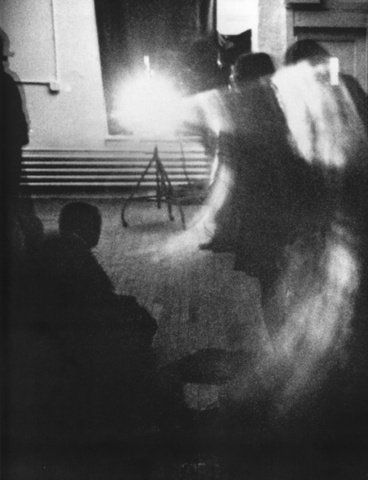

We might be reminded of what Philippe Lançon wrote in Le Lambeau to describe the links between photography and death: “what has been captured ceases to exist the very next second; what we see is the motionless imprint of an instant, of a life that has ended; and even this imprint will fade one day. What we see at the end is the condensation of all these phenomena. It is therefore neither a reality nor a memory, nor a fantasy, nor a dream, nor a ritual of resurrection but a bit of all of them at once”.

As in all their work, this is not, in any case, a dissection or distant contemplation of the archive, nor is it an obsessive aesthetisation. Angela Ricci once recalled that Marinetti had expressed his love of war - the one that led Italy to fascism - with such poetic proclamations as “the pleasure of opening up flowers of blood in the bellies of Ethiopian women”. On the contrary, and once again, it is a mano a mano approach in which the film’s subject matter risks becoming contaminated - or swallowed up - by the ghostly bodies which the images have yet to blur. So what we really see here, the reason for this diptych at every turn, is the journey through the images with which Gianikian manages, by means of projection, to make Angela a presence, for her to continue being present.

Gonzalo de Lucas