Long before cinema came to the museums, filmmakers screened art (their processes, their histories) in the screening room. In 1915, a really young Sacha Guitry filmed Renoir, Monet, Degas or Rodin, the last masters of the XIX century; Man Ray filmed Picasso during his holidays in Côte d'Azur in 1937; Jonas Mekas filmed Andy Warhol close to the sea and Andy Warhol filmed Dalí in the Factory. It was 1966. In half a century, cinema came with (and pushed for) the great transformation of arts, from impressionism to pop art. The screen —as white or blue colours at the origins— could be a window to the workshop of Matisse, Pollock, Cocteau, Bacon o Pasolini; and cinema, as unique and privileged way to be involved in and to keep the memory of the making of art, to document the creator's gestures and the intimacy of his workshop.

If the links between artists can be revealed and screened together, in “thinking art from cinema” we follow again this memory. Instead of searching the analogue relation between cinema and paint, or between cinema and photography, we discover the relationship between these films: they show how they think themselves, how they investigate the possibilities and the limits of their matters and mediums: essays on time, rhythm, edition, artistic medium. They are the underground histories of art.

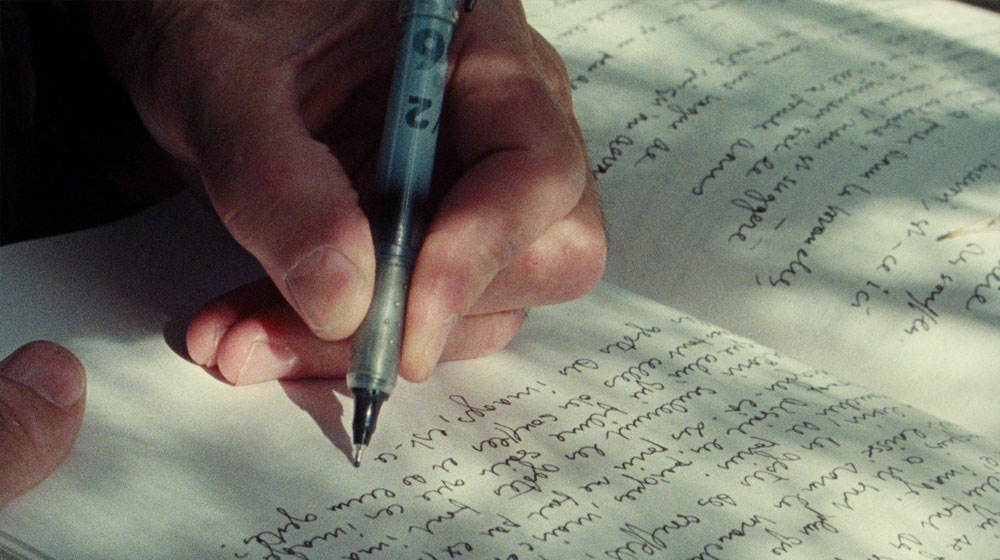

It exist a deep link between Man Ray's camera and Jonas Mekas's Bolex, or between Sacha Guitry's photography with a editing projector close to his bed, or Godard's images watching again images from Passion in the editing room. This is because all of them appropriates the cinema's tools (camera, editing projector) to essay an own writing, as a logbook or a draft book.

Away from conventional cinema and industrial forms (of duration, genre, etc.), in a loft in New York, in a edition room in Rolle or in the Villa Santo-Sospir, a group of artists investigate their creative processes. In this daily space (laboratory, bureau, studio), Godard reflects on “old art”, Cocteau reflects on colours and traces of the film, and they do it with their specific medium: film, paint, frames, durations.

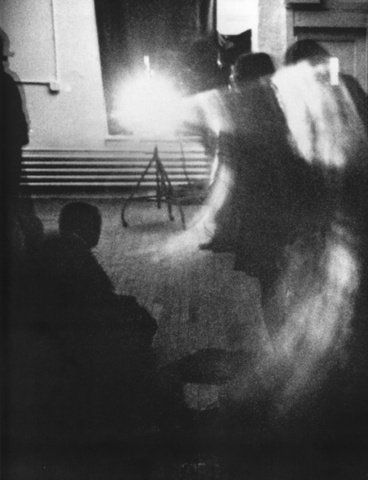

One of the most beautiful qualities of cinema is the capacity to be evident and mysterious at the same time, to let us see things (leave a document, a mark, an evidence) and also to let us go to our memories and transfigurations; to think ourselves at the same time that we avoid any reflection. A little time before to begin doing films, Godard discovered in Eléna et les hommes, by Renoir, a principle that nobody embodied as much as him: «art and art theory at the same time. Beauty and the secret of beauty at the same time. Cinema and explanation of cinema at the same time». This is why we begin this programme with an imaginary dialogue (of images and sounds) between Pasolini and Godard, and their own explorations: Pasolini looks for the landscapes and faces of an archaic world to his project Il Vangelo secondo Matteo; Godard looks for images free of verbal, for ways to look and to know. After that, we come close to the camera testing what Renoir made with Sylvia Bataille before the beginning of the shooting of Une partie de campagne, Godard filming Brigitte Bardot in Le Mépris, the Straub moulding every Kafka's word, and Chantal Akerman essaying rhythms, dances and voices. These pieces about films in process or the process of filming make us closer to the filmmakers gestures and their creative concerns.

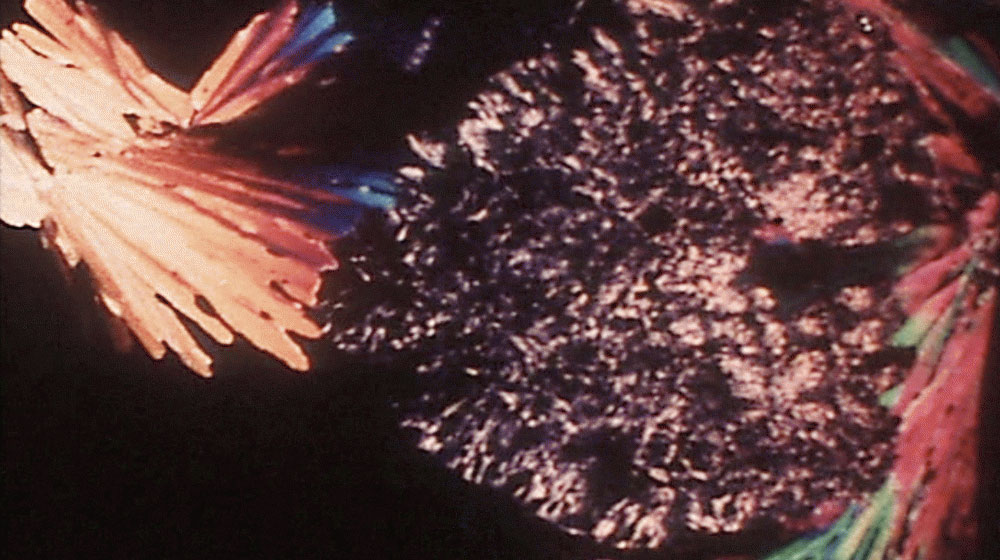

Suddenly we found that these films exceed borders or categories separating arts because they work with specific values and matters. They show us the way in which since the 1920s cinema, photography and art did not stop to think themselves mutually, reinventing themselves with their own contributions. In the same way that cinema re-invent itself when it explores and finds ways to get close to art (essays, diaries, portraits), it also happens when an artist appropriates and transforms it. Sometimes, it happens through private experiments or home movies, as in the case of Magritte or Man Ray, with their divertimento; in other occasions it happens through the transition from an art to another, as in the case of Robert Frank or Michael Snow, from photography to cinema (to find it again, at the end of the road); and it happens also through an essay getting close to other ages (Delvaux and the XV century paint) or the re-appropriation of the other art gestures (Brakhage paints on celluloid and dialogues, among others, with the Monet and the impressionist's traces).

Every session explores one way to look at the way of the artist (filmmaker, painter, photographer) to work with his images —he looks for them, he thinks and leaves them, he rectifies, superimposes and contrasts — or he dialogues with loved images of other artists. Every session, revealing the relations between films or tracing a little history of the forms, proposes an itinerary on the way in which cinema thinks, around itself or in its relation to art.

Núria Aidelman and Gonzalo de Lucas