The films of the Colectivo Cine Mujer erupted in the Mexican cinema of the 1970s and early 1980s like a flash of lightning, capable as they were of imagining new forms of filmmaking and political intervention. There’s been no other movement like it, before or since. It appeared at a time when the representation of women lay somewhere between "auteur" cinema and Mexico’s “cine de ficheras” or sex comedies that provided a combination of nocturnal spectacle and erotic comedy, in which the idea of female desire was forged by contrasting saints and femmes fatales. Conversely, the filmmakers of the Colectivo Cine Mujer explored the systematic oppression of women from a personal dimension, such as the routine of a housewife, but also from a cultural, medical and judicial perspective by recording the first-hand accounts of doctors and directors of prisons for sex workers. In line with the ideas of the second wave of feminism, the personal is political. It was political then and is still political now.

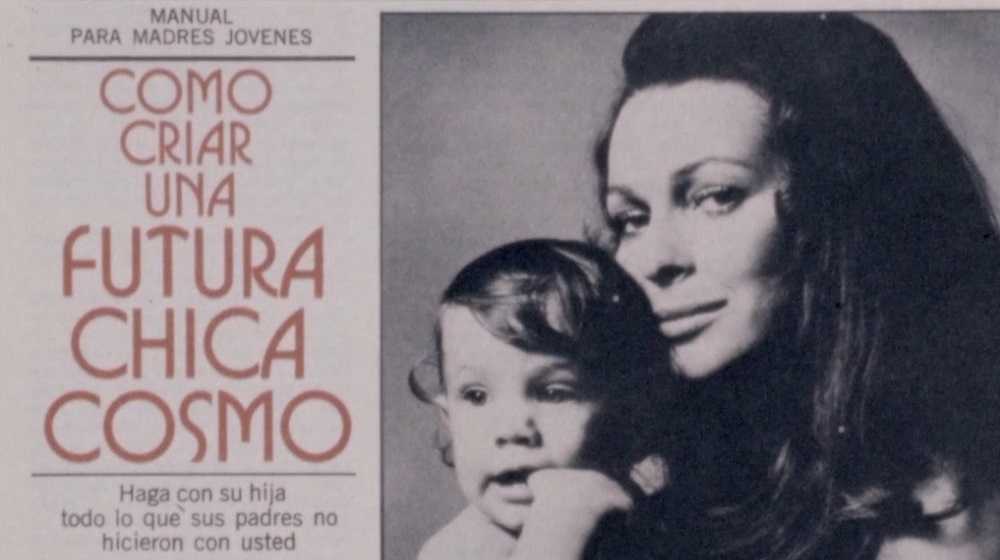

The concerns that propelled the Colectivo in its early years are still painfully present today: the mandate of femininity in a consumerist world (¿Y si eres mujer?, 1977), the decriminalisation of abortion (Cosas de mujeres, 1975-1978), the recognition of household work (Vicios en la cocina, las papas silban, 1978), sexual violence associated with virility (Rompiendo el silencio, 1979) and the stigma of sex work (No es por gusto, 1981). The Colectivo’s filmmakers recorded the political mobilisation of different women in various parts of the country. From Oaxaca to Tijuana, they filmed domestic workers, embroiderers and textile factory workers because they believed the struggle of women has always been linked to the class struggle.

In dialogue with its time, the Colectivo was founded by the Mexican Rosa Martha Fernández and the Brazilian Beatriz Mira, later joined by Guadalupe Sánchez, Ángeles Necoechea, Sonia Fritz, Eugenia (Maru) Tamés Mejía and María del Carmen de Lara, among others. It emerged during the student revolts of the late 1960s and the political urgency that brought together the so-called New Latin American Cinema. Like this cinematic earthquake, the Colectivo also questioned how reality was being recorded. The inclusion of fable in the narrative is highlighted in various ways, such as illustration, collage and the creation of fictional characters from interviews. The decision to show clandestine issues, such as abortion in Cosas de mujeres, shakes up the conventions of the traditional documentary and is a wake-up call for audiences.

I’d like to quote Rosa Martha Fernández from an interview in 1980: "We try to ensure our contribution disarms [...] those codes that solidify the oppression of women, and to do so we have to unravel what’s apparently "natural" in their marginalisation: to show the political, economic and cultural interests that cause women to be in the state they’re in". This contribution involves both an aesthetic and a political quest. Cosas de mujeres begins as a fictional tale about a young woman who only has a friend’s support to go through with an abortion, but the film ends as a documentary that shows how the Mexican public health system and state operate. In voiceover we hear fragments of the penal code while we see various women in a hospital at risk due to clandestine abortions. Reality disrupting fiction is used as a "strategy to disarm". It obviously demonstrates cultural interests but also cinematographic form by creating a distancing effect. The Colectivo mentions its closeness to the ideas of Bertolt Brecht in various interviews. The notion of a strategy to disarm reminds me of the “Kino Fist” of Sergei M. Eisenstein, also influenced by Brecht. Regarding this Soviet filmmaker, the critic Gilberto Pérez writes: "By making us notice the cuts, Eisenstein was trying to make an impression on us that intensifies our reactions, to hit us hard". In a similar way, the Colectivo’s films also sought to achieve that kind of blow, an invitation to make us "open our eyes".

Another distancing or disarming strategy can be found in how the Colectivo used sound and music. Forming part of a sentimental education, boleros seem to cross over various Latin American territories. Dominican Luis Kalaff Pérez's song "Aunque me cueste la vida", performed by Alberto Beltrán with the Sonora Matancera, originally from Cuba, opens Vicios en la cocina, las papas silban. Music and a radio soap opera accompany the daily routine of a woman who talks about married life and raising children whilst carrying out various household chores on a day like any other, a day that ends with waiting for the husband to come home, a figure permanently out of shot. The music functions as a counterpoint between the voice and poetry of Silvia Plath, whose poem gives rise to the film's title: "Viciousness in the kitchen! The potatoes hiss. It is all Hollywood, windowless". The sound accompanies the image which, as in the collage of ¿Y si eres mujer?, provides an account of this female world expressed through motherhood, domestic work and waiting, an experience also filmed by another women's collective in Colombia in the short ¿Y su mamá qué hace? (1982).

In an interview with Beatriz Mira, the director highlights the teamwork involved in choosing both the music and staging. In fact, the idea of using poetry and popular music came up in one of the meetings in which feminism and film were being discussed. Popular music has been a constant throughout the life of the Colectivo. The bolero and songs by Violeta Parra, Los Tigres del Norte, La Sonora Dinamita and Daniela Romo mirror the concern for grassroot struggles that particularly influenced Colectivo’s second active stage, in which the work carried out by groups such as the Cooperativa de Cine Marginal and the Taller de Cine Octubre, which also saw film as a political tool, was vital. In Yalaltecas (Sonia Fritz, 1984), the Colectivo Cine Mujer filmed a group of women mobilised against the local authorities in a region of Oaxaca, while Vida de ángel (Ángeles Necoechea, 1982) recorded the experiences of different women in a colony in the south of Mexico City, their organisation in the colony and domestic routines, occupied by married life and raising children.

In Vida de ángel there’s an animation sequence that serves to evoke the desires of working women, such as seeing the sea. Animation is used to visually represent dreams and imagination. In a way, it’s also a return to the early years of the Colectivo (¿Y si eres mujer?) with an emphasis on manual labour reminiscent of the films of Norman McLaren. In this respect, Guadalupe Sánchez talks about always having been "very handy", as well as her relationship with the images of her adolescence: the paintings of Rembrandt, Remedios Varo and the images from Life magazine, with which she made her 1977 short film. It’s as if the hand intervenes in what catches the eye; the result is an exercise in imagination through cut-out and collage. In the short, the hands of Sánchez and Carlos Bustamante (in charge of the cinematography) intervene in the drawing, dressing the girl in the film to show how gender roles are imposed by factors external to ourselves, such as the political and social conventions that "solidify our oppression", in Fernández's words.

The intervention in the cinematic form present in the three films that make up this screening (¿Y si eres mujer?, Cosas de mujeres and Vicios en la cocina, las papas silban) constitutes a strategy to disarm but also an approach to political intervention in cinema. In my opinion, Rosa Martha Fernández's idea of cinema as "an instrument to transform reality and raise awareness", a beacon of 1970s cinema, is still valid. If the political sense of struggle through form has been lost, then it’s important to return to these films and throw some light on their proposals, today more than ever. What remains today of those “intervention films” that disrupted Latin American cinematography? Such films display formal ideas that once helped to open our eyes and destroy our firm beliefs; ideas that, today, can help us to illuminate the darkest nights. Now, as then, the films of the Colectivo Cine Mujer are a flash of lightning that allows us to see clearly what we’ve been merely glimpsing: namely that form, and not only theme, is revolutionary.

Karina Solórzano