Film the “rhythm” of truth

Jonas Mekas, Out-takes from the Life of a Happy Man

The reader should be carried forward, not merely or chiefly by the mechanical impulse of curiosity, or by a restless desire to arrive at the final solution; but by the pleasurable activity of mind excited by the attractions of the journey itself.

Coleridge

In a conversation that he had with Jonas Mekas, Stan Brakhage said that he tried to focus on biographical elements in his classes so that the students could sense the emotional and physical movements that lay behind artists’ work. He recalled his wife, Jane, who helped him to perceive this potential (“she is capable of literally describing the physical appearance of a person while listening to a piece of music or looking at a painting”). And, although he initially found this somewhat stupid, over time it became key for him: “I want to achieve a vibrant sensitivity through listening or reading.”

In the sixth chapter of As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty (2000), Jonas Mekas points out to the spectators: “you expect to discover more about the star, in other words, me, the star of this film. So, I don’t want to let you down. Everything I want to tell you is here. I appear in every shot in this film. I’m in every frame of this film. All you need to know is how to read these images.”

Not long after he arrived in New York in 1950 as an exile, having been through various forced labour camps for refugees, Jonas, from his earnings from working in the factories, bought a Bolex camera with his brother Adolfas. From that day on –although for a long time it was done subconsciously, until Walden– he undertook one of the most original film making paths in the history of cinema, a diary covering more than forty hours of completed film, with images shot from 1959 until his death in 2019. (“In reality, all my filming work comprises just one film. I don’t really make films: I just film. I’m a filmic professional, not a film-maker.”).

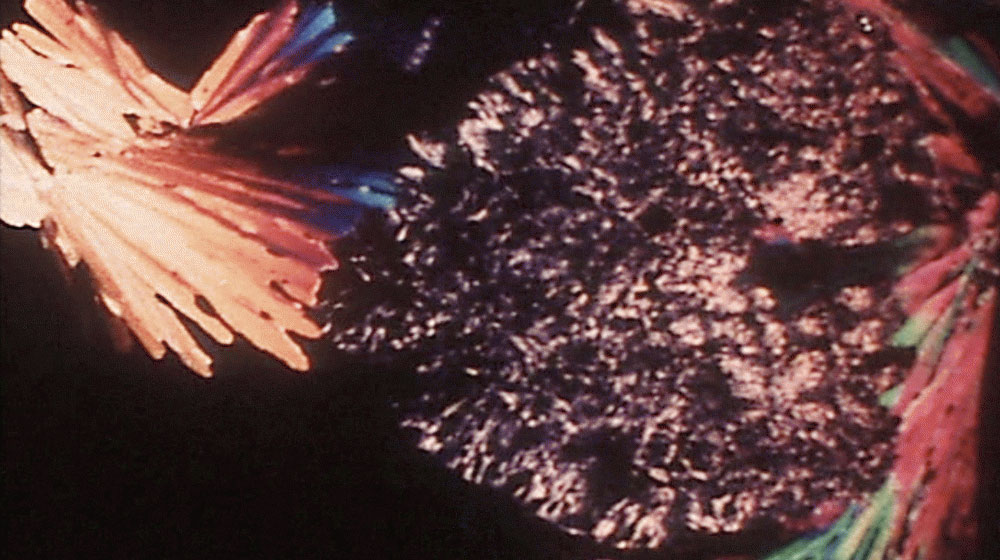

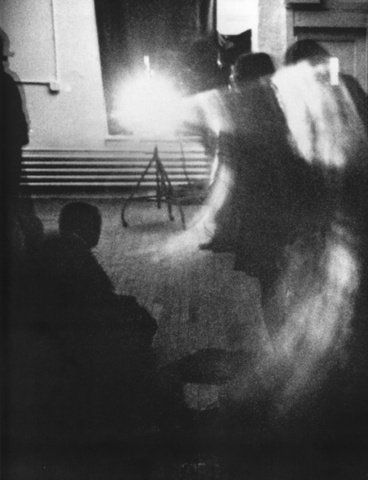

This refining and registering work of including his own body and shape in the images, achieved through filmic actions in the shooting and editing, was his lifetime work, a life reflected in traces of photosensitive film. He used an original method in the history of art, making use of specific aspects of film medium, showing life, not narrating it, through appearances and composed within framed possibilities within the frame (that limit or window which cinematic poetry can open by expanding and boosting its fragmentary nature). This was followed by its sequence in the file, the writing of the production, the projection; the flicker of photosensitive particles, the pointillistic traces of light which Mekas pursues like glimmers, glimpses, just like a child trying to catch snowflakes. That transience which he embraces without worrying about stopping or pausing, showing us exactly what gets out of hand through nervous reaction in the takes – trembling, shaky, jittery - poor focus, decentralised, overexposed. All of these remind us of Chris Marker’s comments on filming happiness in Sans Soleil, through images of three children in a meadow in Iceland: “I retook the whole scene, adding this slightly unfocused ending, this shaky frame due to a strong wind blowing in the cliff face. Everything that I’d got rid of to make it sharper and better explained than the rest… what I saw in that instant because it was within reach, within reach of the zoom right up to its last 1/24 of a second”.

As Patrice Rollet observed, perhaps Mekas’ images shouldn’t be considered so much memories as physical realities, visible presences: “when Mekas holds them in his hands or looks at them in the editing room, it is here that those images, those mnesic traces, inscribed in the memory, are real, actually more real in the end than his own memories which fade over time”. And in a comment by the film maker himself in Out-takes…: “Who cares about memories? No, memories don’t matter to me, but I like what I see, what I filmed with my camera – and now, it comes back, it’s there and it’s all real. Every detail, every second, every frame is real and I like it, I like what I see. Why wouldn’t I show, share these images with you, the reality of the images?”.

Maybe Mekas’ work, rather than a memory test –let’s not start calling it melancholy introspection yet– is poetic art on gestures of filming reality, to later contemplate those gestures, such as freelance writing on moviola and projections. Nothing more, but nothing less, than what can be seen on the surface. Mekas already foreshadowed his cinematic intention when writing in his diary in 1952: “The twentieth century (or was it the nineteenth?) produced Freud and Jung: delving into the unconscious. However, it also produced cinema where man is represented and defined by what he sees, by the surface, and in black and white: as if it mistrusted both Freud and Jung. Surface says it all, there’s no need to analyse dreams: everything is in the face, gestures, in reality nothing is concealed or buried in the unconscious. It’s all visible… they call Hollywood the place of dreams. No, it’s exactly the opposite”.

It may be worth considering how these gestures came about then, what sort of flight, perceptive broadening, could have pursued that exile and labourer arriving in New York. In I had nowhere to go, he noted his sensations at different times while working in a factory, how his hands were imprisoned by the routine of the production line. On the 7th of June, 1950, he wrote: “most of the time they put me on the machine that makes screws: my hands work on their own, automatically, and my brain has nothing to do. So I think about everything, in each minute detail, right through the day; then I start to distance myself, to dissolve myself in dreams, in plans.”

Towards the end of his life, and at the interview he granted us for the book Xcèntric Cinema. Conversations on the creative process and the filmic vision, Mekas responded to Pip Chodorov regarding improvisation: “It’s about being very open, very open to the momento of when you do it, very wakeful, very much in touch with your tools and reality around you, the canvas, the brush, the camera, the stone, the fingers, the beating of your heart, and the nothingness, the silence. It’s like meditation. Getting rid of everything and trying to attain a state of nothingness from which then everything emerges. All my life I worked on it. All the books that I read in my five, six years of wartime and post-war camps. I was polishing, preparing myself. But when I got my first Bolex, in early 1950, I suddenly felt I knew nothing. The camera didn’t want to say what I wanted to say. It went its own way. I felt like an idiot. It was like training a young wild horse. So yes, I’m not exaggerating, it took me some seven, 10 years to free myself from the styles and subject matter, the direct imitations of others, and to master my camera to a degree that I could begin to record what I was recording in a way that when I looked at it later I wouldn’t feel like: what the hell is this! But it not only took me a while to tame the camera, the tool, the horse: it was also the gaining of assurance, the trust in what I was doing. It took me a long time. It was only after I saw Marie Menken films that I knew that I was right in what I was doing, recording, making senseless notes. And it was Lillian Kiesler, after the screening of Walden at her home, who told me that I shouldn’t be apologizing for my single-frame, nervous style, that it was my temperament that I saw and recorded what I was recording, and there was no escape from it.”

On thinking about some implications of the ideas that this camera apprenticeship experience raises when used as an instrument to find actual vision and presence, poeticizing technique, I recalled that conversation that Mekas had with Kubelka. They were discussing how we appreciate beauty so much because it’s critical for our survival, and in that passage where Kubelka says to him: “I always try to go back to the sources of each field that I’m working in. And the conception of art that most people have is a romantic one, that 19th century art that we associate with brilliance and skill, for work carried out and which others applaud. But the different fields of art are countless. You can be a street artist, master how to show things or food. For me, art is a way of articulating existence: it’s an articulation of the way someone views the world, or the world they understand it. And this articulation should be applied through the media”.

One would say that Mekas’ films didn’t intend to undermine visible presences in order to extract some occult mystery; they were full of doubt about what he saw, but also driven by a pleasure and enthusiasm which, just like those Soviets from the 20s, were celebrating a new space of visibility or for vision. In his case, he patiently cultivated or sowed, which would further develop his idea as a film maker – the stroke, the diary-style gesture – through insistence and perseverance, and in various forms, portrait, poem, home movies, sketches…

During all of this time, the nucleus, the heart of his filming presence, in pursuit of true rhythm - the empowered gestures, liberated from production lines – was always the same, a daily sustained approach in poetic chant form, to that photosensitive nature that shaped his century. It was the broken appearances, frames that the film maker edited or grouped together at random, with no fixed chronology, and that in the end weren’t so much of an autobiographic projection as work that was material, physical. But it had a rare type of substance – film – perhaps similar to those precious gems Walter Benjamin spoke about: “The separated images of his initial contexts are like precious pieces in the inner recesses at the back of our minds, they’re like fragments or torsos in a collector’s gallery (…). Memories… don’t always make up an autobiography… Autobiography is to do with time, with its passing and whatever the continuous flow of life holds. However, here, I’m talking about a place, specific moments, and gaps”.

On the day that Jonas Mekas died, I had actually shown a projection to my pupils in class, a fragment of As I Was Moving about snow and paradise. They were not very familiar with avant garde cinema, and it was wonderful to see the way they connected emotionally, how they felt and associated those images with his previous personally revealing films and the creative potential of those minimal gestures, exactly the principles of montage and creation that we were trying to work on. As I was going home, I considered yet again how Mekas’ cinema which, at the time, and as Stiney recognised, hardly anyone imagined would endure, is now looked on as such a close vision for them, and how they have adopted intuitive and normal images early on that relate to their own lives. That afternoon, I learned of his death, and I thought again about how film draws us close to everyday norm, so that every one of us can see differently: “Without knowing, unconsciously, we hold… every one of us holds, somewhere deep within ourselves, some images of paradise”, “some fragments of my world, of my world that is not so very different to that of anyone else, to anyone else’s world”.

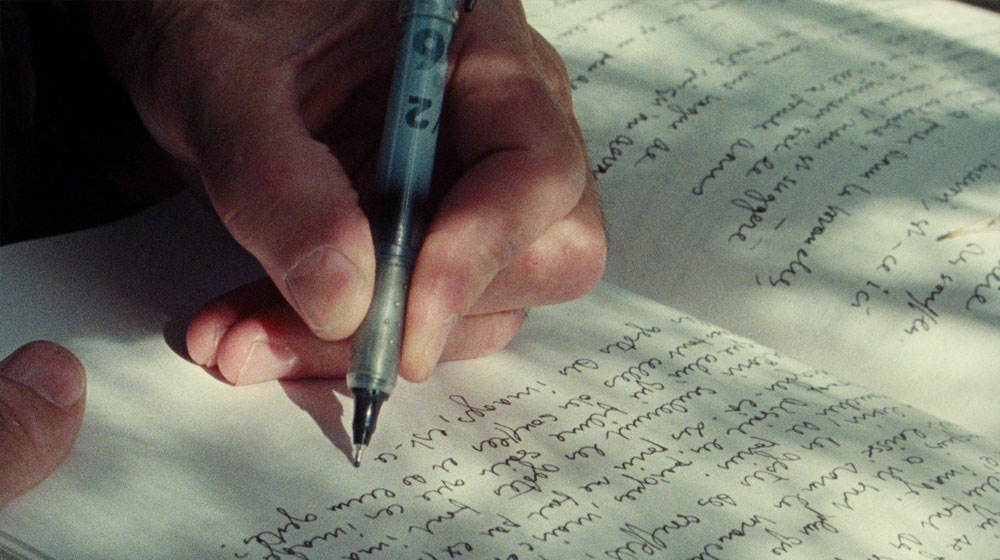

He aptly cites Mae West’s quote on a poster for He Stands in the Desert Counting the Seconds of His Life: “You keep a diary and the diary will keep you”.

Gonzalo de Lucas