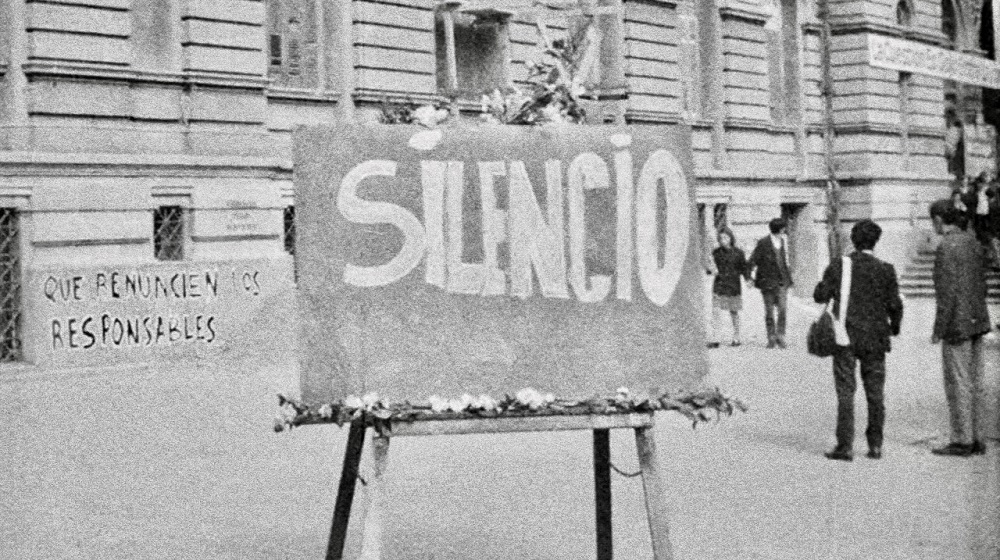

In a scene from Kino und Opposition (1970), the critic and programmer Peter B. Schumann interviews Uruguayan filmmaker Mario Handler inside the premises of the Cinemateca del Tercer Mundo (C3M) in Montevideo. In the background, Octavio Getino and Fernando Solanas, members of the Argentinean group Cine Liberación, whom Schumann will also interview in this film made for German television and devoted to Latin American political cinema, can be seen acting as extras. The small room is crammed with film cans, loose spools of film, projectors, lab lights, a vertical rewinder, developer, old cameras, reels and cables hanging on the walls. Handler tells Schumann about the working conditions at C3M and exemplifies this with details of how his "most successful" film, Me gustan los estudiantes (I Like Students) (1968), was made. He says they’d got hold of newsreel footage of the recent student riots in Montevideo; however, they didn’t have any access to professional editing equipment, so the method they used consisted of viewing the footage on a projector, using scissors to cut the film, scraping the edges with a simple razor blade and splicing the film back together manually with adhesive - an entirely handmade process that took many hours of hard work although the film was short.

This anecdote can help us realise the radically limited resources that characterised the Latin American political cinema in the 1960s and 1970s. Born out of the urgent need to seek connections with societies that were increasingly impoverished and oppressed by the authoritarian regimes of the time, militant films were always made under difficult conditions: a lack of technical resources led filmmakers to reuse equipment discarded by the film industry or to put equipment to a use other than that for which it had originally been designed. They were usually self-financed films which only occasionally benefitted from investment obtained via ticket sales or prizes won at festivals. And, of course, they were clandestine, made by persecuted filmmakers who’d get together in basements, garages, attics or camouflaged public spaces to carry out their work. Many of the films were made using pre-existing material that came from whatever sources were available in the popular media, such as magazines (La Paz, María Elena Massolo/Cine Liberación), radio programmes (Refusila, Grupo Experimental de Cine; Caracas dos o tres cosas, Ugo Ulive) and television (TVenezuela, Jorge Solé), and even other films (Ya es tiempo de violencia, Enrique Juárez) – the use of all these materials being underhand, without seeking permission and endowing the works with an experimental approach that allied them with the collage and avant-garde cinema of the same period.

This shortage of resources resulted in a particular style and discourse but it also affected how the films were distributed and preserved, and how they survived. Latin American political films from the 1960s and 1970s have been scattered and lost, just as their filmmakers were forced to live in secrecy or exile, or were imprisoned and sometimes tortured, in other cases even assassinated or simply “disappeared”. Many of the films have disappeared with them and, today, only oral records or mentions of their existence in catalogues or press releases survive. Some of the films were censored and confiscated by the local security forces whilst others were voluntarily destroyed by relatives or friends who were afraid the repressive regime would find them. Some films were lost during their makers’ journey out of the country, or after an impromptu screening in a hazardous location.

Many of the militant films that survived did so abroad, being sent for screening at festivals interested in the Latin American cinema of the time[1] . Others were safeguarded by organisations or individuals who formed part of a network sympathetic to the cause and the people involved, almost always involving a certain degree of informality that makes it difficult today to trace their circulation and origin. Sometimes they survived in film archives under a covert identification that concealed their real title or authorship, as pointed out by Isabel Wschebor in the case of some films from the Cinemateca del Tercer Mundo[2] . On other occasions they were clandestinely and privately kept by the filmmakers, in a hidden stairwell, between the walls of a house, behind the plaster of a wall. These were hidden films or “películas escondidas”, as Fernando Martín Peña called a number of recent discoveries of Argentinean films that have appeared after being concealed for decades; waiting, crouched, for the historical moment to appear.[3]

The image conjured up by such appearances is one of a dispersed and fragmentary archive. Only a small part of what existed has been preserved but, moreover, what has been preserved is often not what best represents the status of the original work: faded, worn and scratched copies, incomplete films, scraps of raw materials from films that were never finished but once imagined. It is rare to find the original negatives, the source material favoured by film restorers to return a film to its originally conceived form. However, in spite of this incomplete archive, this survival of militant cinema is capable of raising questions regarding the very notion of film preservation itself. If these films hadn’t aroused the interest they’re enjoying today, it’s perhaps because these works have been perceived as of little relevance by the decision-makers in film archives, who are influenced by the paradigm of "film as art"[4]. The recovery of Latin American political cinema has been a tireless activity carried out by researchers, historians and independent collectors and not so much the result of programmes promoted by institutional archives or national film archives. These worn-out films, whose only copy is sometimes a poorly transferred magnetic video, are uncomfortable both because of the condition of the surviving materials and also because they contain the memory of a period of history that some prefer not to revisit.

The concept of cinemateca (a cinemateque or film archive, sometimes with a venue for screening) also plays its part in this debate, becoming almost a link between those filmmakers of the 1960s and 1970s and the archivists of the present. The aforementioned Cinemateca del Tercer Mundo in Uruguay was one of the most relevant alternative cinematecas to emerge in Latin America in the late 1960s. Contrary to what we normally understand by the term cinemateca (or filmoteca in Spain), these alternative cinematecas were involved in screening, producing and also distributing films. Use of the term cinemateca sought to openly question the role played by the institutions that would bestow social and cultural value to films. These third-world cinematecas[5] provided an alternative place for films to circulate, showing works that would never be screened in commercial cinemas. As a result, they shared a tradition that had already been started by the national film clubs (cineclubes) and cinematecas of the time, which were also dedicated to showing non-commercial cinema. However, while the latter showed works of high artistic and cultural value from the past, these being mainly European auteur films whose copies came from the official exchange networks linked to the International Federation of Film Archives[6] , the alternative cinematecas showed political, avant-garde and contemporary cinema. The list of filmmakers and works being screened made up a relatively homogeneous corpus, infected by the revolts and worldwide revolutions of Cuba, Vietnam, the May 1968 riots in France, the American Black Power movement, the resistance against Latin American dictatorships and the pan-Africanist liberation struggles[7]. In the face of the primary cinema of the commercial cinemas and the secondary auteur cinema of the cinematecas and film clubs, the alternative cinematecas encouraged the production, exhibition and preservation of a third, counter-hegemonic cinema.[8]

This debate in the late 1960s regarding the circulation and canon of films, as well as the legitimising effect of films being preserved as “heritage”, is still alive today. Returning to work on such films today forces us to think again about their presentation and archiving, both practices being trapped today in the market of audiovisual content. Perhaps these types of cinema can also encourage us to think about a cinema and a world that’s possible to inhabit, with the contagious force of that radical imagination.

[1] The film La Paz, made in 1968 by María Elena Massolo as part of the Cine Liberación group, was recently recovered. The only known copy is kept at the Arsenal Institute for Film and Video Art and was recuperated in 2024 as part of the research project "Segunda mano" (Second Hand), coordinated by Carolina Cappa at the Elías Querejeta Zine Eskola.

[2] Wschebor Pellegrino, Isabel. "La Cinemateca del Tercer Mundo en Uruguay (1969-1973). Una posible arqueología de sus archivos". En La Otra Isla, No. 10, 2024.

[3] Peña, Fernando Martín. "Películas escondidas", series of articles for El Cohete en la Luna [blog], 2020.

[4] Fossati, Giovanna. "For a global approach to audiovisual heritage: A plea for North/South exchange in research and practice". Necsus, Autumn 2021_#Futures. https://necsus-ejms.org/for-a-global-approach-to-audiovisual-heritage-a-plea-for-north-south-exchange-in-research-and-practice [accessed 06/09/2024].

[5] Other initiatives adopted similar names, such as the Cinemateca del Tercer Mundo in Buenos Aires, the Comité para el Tercer Mundo, the Colletivo Terzo Mondo (C3M), and Distribuidora del Tercer Mundo (D3M), the Venezuelan branch of the Uruguayan C3M, which played a key role in exchanging and circulating films.

[6] Tadeo Fuica, Beatriz. "¿Qué mostrar? ¿Cómo cuidar? Análisis de colaboraciones entre incipientes cinematecas para enfrentar dilemas comunes durante los años cincuenta". Encuentros Latinoamericanos, Vol. IV, No. 2, July/December 2020.

[7] Lacruz, Cecilia. "La comezón por el intercambio", in Mestman, Mariano (ed), Las rupturas del 68 en el cine de América Latina. Akal, 2016.

[8] Getino, Octavio and Fernando Solanas. Cine, cultura y descolonización. Siglo XXI Editores, 1973.

Carolina Cappa