In his films, Luke Fowler (1978) uses the past as a set of tools to create, in the manner of a kaleidoscope, provisional structures from "residues and debris of events (...), fossilized witnesses to the history of an individual or a society1". Tracing through the different layers of collective memory and its artefacts, the Scottish filmmaker operates with what he has to hand, like a bricoleur. He takes existing elements such as diaries, notes, sketches, voices and images, and juxtaposes them so that micro-stories and vernacular narratives told by subaltern voices arise up from their fragments. In this way, the images and sounds of his films are not timeless or an abstract refuge but a "historical presence"2, a conception that distances his films from aesthetic formalism, detached from social structures, and links them to the social conditions of production, to the interactions and spaces of struggle, and to life in general.

This is a materialist approach in two senses of the term. Whereas, on the one hand, Fowler sets up a dialogue with the past by retrieving certain forgotten figures, on the other his work is based on the technical conditions of cinema, presenting the material aspects of the filming process in his films. By introducing his tools of the trade - the camera, light meter, lenses and microphones - the filmmaker clearly reveals the place where his works are expressed. At the same time, this place is not arbitrary but related to the filmmaker's environment and background. Fowler was born and lived in Glasgow, a working-class city where, in addition to the shipyards and textile industry, there is a strong socialist tradition related to its university. His Marxist upbringing and the fact that he was also a musician endowed him with a profound sense of democracy, present both in the non-hierarchical way he treats his collaborators and also in the 'free' way he structures sounds and images and how he relates to cinematographic conventions and genres3.

For Fowler, film is a kind of research that involves intense archival work and goes through all the stages of creating a film and can even continue afterwards. A process of constant exploration in which he retrieves memories4, characters or events that have remained hidden in history. However, many of these materials do not speak for themselves, while others are not neutral transmitters of information but have their own ideological structure that must be brought out5. All this requires work - editing and juxtaposing different elements to open up the documents to multiple possibilities of transformation6. To demonstrate this work, we're focusing on three films, Houses (2019), Mum's Cards (2018) and To the Editor of Amateur Photographer (2014), which are the result of Fowler's encounter with different archives: that of the filmmaker Margaret Tait, his mother's reading notes, and the archive from the feminist photography centre in Leeds. In these works, the various documents present the story in fragments with the voice of their protagonists and their embedded records.

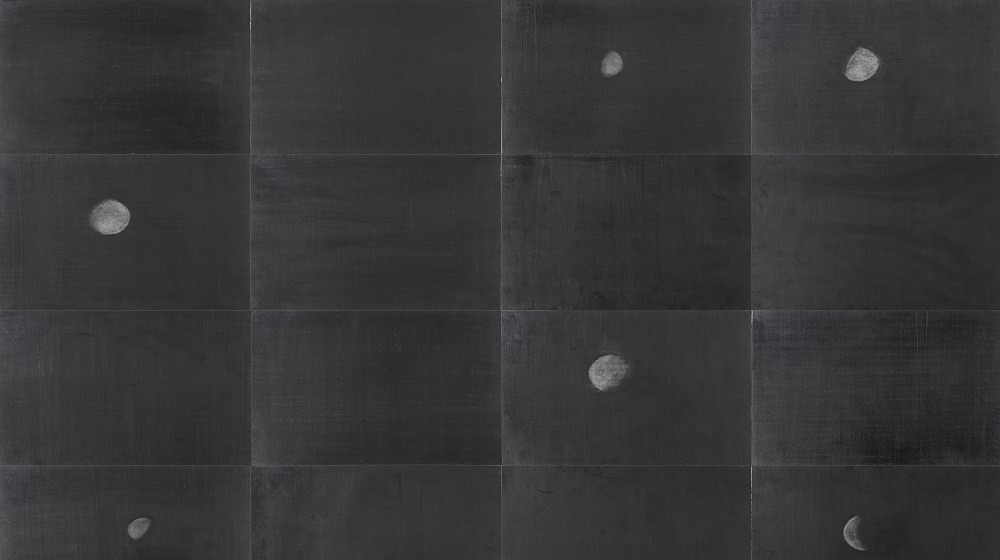

Like Anton Webern's short pieces, which are aphoristic in structure, Houses provides a highly concentrated summary of what cinema is for Margaret Tait, reviewing some of the recurring motifs in her films-poems: the walls and windows of her studio, the poppies growing by the side of the road and the paths and stairs that lead to some of her houses. For this Fowler went to the Orkney Islands, the archipelago where Tait was born and where she created part of her work and, as well as trawling through her archive, recorded images and sounds of the landscape, the houses where the Scottish filmmaker lived and the places where she filmed, those tiny landscapes7 that she so loved to "stalk" with her Bolex, in which "an apple has no less intensity than the sea [and] a bee is no less surprising than a forest8". These micro-landscapes are interwoven with filming notes, reflections on sound or observations on the relationship between women and cinema, among other annotations by the filmmaker9. In addition, a recording of her voice breaks into these images, as she often did in her films, reading the poem that gives this work its title. Houses is therefore an almost corporeal evocation of Tait's life and work, and it doesn't ignore the challenges she faced as a woman making films.

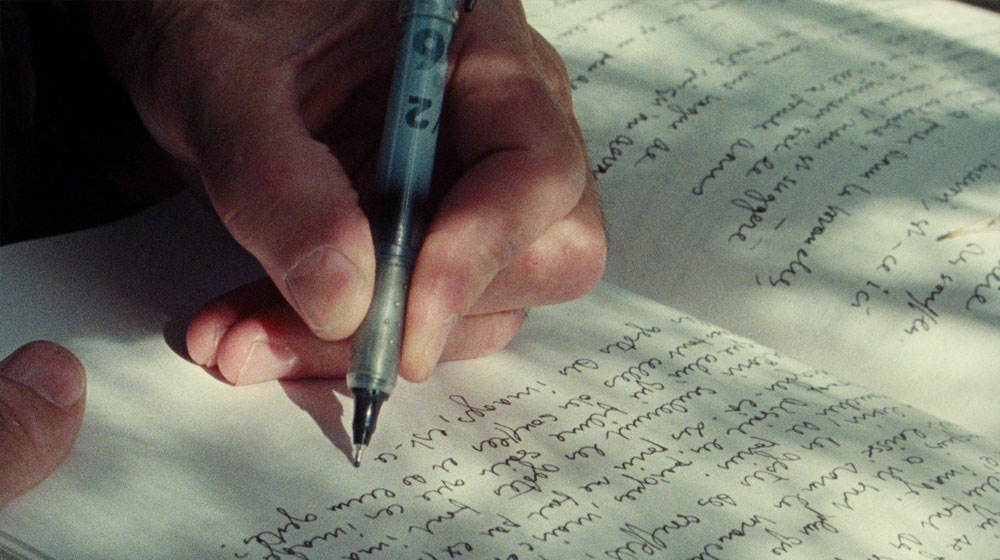

Also using an aphoristic structure and handwritten motifs10, in Mum's Cards Fowler creates a portrait of his mother using the many index cards she used for lecture notes. These notes are signs of research work that remains outside the field, in which the sociologist, drawing on Marxist-feminist thought and social theory, addressed social injustice, the mechanisms underlying the reproduction of patriarchal forms and other hierarchies present in Western societies. These index cards therefore allude to a material time of study in which his mother's body spent hours reading and taking notes. An image which Luke Fowler has embedded in his head and chooses not to show11, but which we can infer by following the curves of her calligraphy or imagine from the vast iconography of women reading. It's precisely these cards, stored in filing cabinets, shoeboxes and among books by Pierre Bourdieu, Émile Durkheim or Max Weber, that allow the filmmaker to create this picture, albeit indirectly. This is no coincidence, since one of the subjects his mother dealt with refers precisely to this imagery, of working-class women reading12, as she herself explains in the film, her husky voice also providing details of the methodology she followed in taking these notes and what it was like to study sociology in the first few years of university.

Finally, To the Editor of Amateur Photographer, a film made by Fowler in collaboration with the musician Mark Fell (1966), revolves around the testimonies and documents related to the complex history of Pavilion, the feminist photography centre in Leeds founded in 1983, in which photography was a powerful educational tool and a means of critical work. In an attempt to approach the complexity of this history and different points of view, the authors interweave extracts from interviews with the centre's founders, scenes filmed at the Feminist Archive North of Leeds University (where the documentation of the first decade of Pavilion is now located13) and field recordings made in Woodhouse Moor, the park where this centre was once located.

In addition to the fragments of oral history and various materials documenting Pavilion's activities during those years, there is another recurring visual motif in To the Editor, namely a set of amateur photographs that evoke the social texture of those political practices and function as a counterpoint to the interviews14. While these images allude to an idea of community, the interviews suggest disagreement and discord. This dispute between voices and images is also present when the interviewees15 describe a photograph used to explain their relationship with Pavilion, an image we don't see synchronised with the narrative, in clear homage to (nostalgia) (1971) by Hollis Frampton. In this way, Fowler and Fell take archival materials and disintegrate them, using their fragments to compose a dense polyphonic mosaic16 with which they attempt to represent the history of this collective in which disagreement and dissidence played a necessarily constitutive role.

Coda

Bushels

Women under bushels,

Extinguished lights,

Women poets

-Poetesses-

You never had a chance, had you?

They either dressed you in blue stockings

Or put you in the kitchen.

You could be gracious

or gossipy

or good cooks

"Motherly," Or, if not that, then "manly," they insisted,

Never strong, feminine, yourselves,

Not that, never that,

Never women, poetesses,

Beings and doers in your own right.

Margaret Tait, Subjects and Sequences, 1960

Celeste Araújo

[1]Claude Levi-Strauss, El pensamiento salvaje, Ed. Fondo de Cultura Económica, Mexico, 1984, pp. 42-43.

[2]Paraphrasing the talk given by Luigi Nono in Darmstadt, "Presenza storica nella musica d'oggi" in 1959, published in Luigi Nono, La Nostalgia del Futuro. Scritti scelti 1948-1986, il Saggiatore, Milan, 2017, pp. 147-154.

[3]See Luke Fowler: Sentido común. Una conversación con Andy Davies, La casa encendida, Madrid, 2013.

[4]Memory is not something inert located inside an archive but is constantly being made and remade. In this respect, see K. J. Rawson, Joan M. Schwartz, Terry Cook and Eric Ketelaar; Archivar, La Virreina Centre de la Imatge, 2017, Barcelona.

[5]This is present in earlier works in which Fowler uses images from the mainstream media to re-examine historical figures, such as the Scottish psychiatrist R. D. Laing, the composer Cornelius Cardew and the Marxist historian Edward Palmer-Thompson.

[6]See Son[i]a #284, Luke Fowler, Radio Web MACBA, https://rwm.macba.cat/en/sonia/sonia-284-luke-fowler.

[7] "When I was in Orkney, researching a film about Tait, I was struck by how sublime the scenery is: the cliffs of Yesnaby, the white beaches, the ancient standing stones. Yet, very rarely do you see these types of awe-inspiring views in Tait's films". Fowler, Luke; "My influences", in Frieze no. 206, October 2019.

[8] In an interview she gave in 1979 for the BBC Spectrum series, Tait quoted an excerpt from a lecture on Góngora by Lorca to explain how, in her films, all elements are equally important.

[9] I have transcribed some notes by Margaret Tait which can briefly been seen among the images of this film: "Since 1954 I have been producing short films independently in Scotland (...). Photographing, editing myself has given me an intimate knowledge of the structure of the film. (...) This morning I spent 2, 3, 4 hours [with] stop motion pictures (...) I was especially conscious of the character of the light minute by minute (...). The film description of a certain place, a certain periphery, its ramifications, branches... my own personal tendency. (...) I don't really think that should have any music, but just comment and natural sounds (...). We don't live forever (...)".

[10] These handwritten texts or sketches are a recurring motif in Luke Fowler's films, a kind of indirect homage to Robert Beavers and his film From the Notebook of... (1971).

[11] "I have an ingrained image of her at the kitchen table late at night, reading, writing and smoking roll-ups". Fowler, Luke; idem.

[12] Fowler, Bridget, The Alienated Reader: Women and Romantic Literature in the Twentieth Century, Harvester Wheatsheaf, New York, 1991. A book devoted to the social role of popular literary genres and the ethnographic study of their reception.

[13] Pavilion is no longer a feminist organisation dedicated exclusively to photography but a cultural and artistic centre. In fact, this film was commissioned by the centre on its 30th anniversary.

[14] These photos were developed from 1,200 negatives found by the authors among documentary sources. Both these images and the unabridged interviews were added to the documentary collection of Feminist Archive North.

[15] When filming the interviews, the authors took into account the politics of representation and a participative approach was taken to how they were portrayed. It was the women themselves who decided how they wanted to be shown on screen and where they wanted to be filmed. In this respect, it was also important that the film was made with the help of filmmaker Margaret Salmon, who recorded the interviews. Her presence behind the camera, fleetingly expressed, has political significance.

[16] It was this musical montage that allowed them to structure the different sound and visual elements. According to the authors, the music produced by Fowler and Fell, to set up a dialogue with the different materials filmed in the feminist archive, has very clear links with the history of Pavilion as it alludes to the electronic music made in Leeds in the early 1980s and also evokes other political movements of the period.