The cinema was the typical survival-form of the Age of Machines. Together with its subset of still photographs, it performed prizeworthy functions: it taught and remind us [...] how things looked, how things worked, how to do things ..., and, of course [...], how to feel and think.

Hollis Frampton[1]

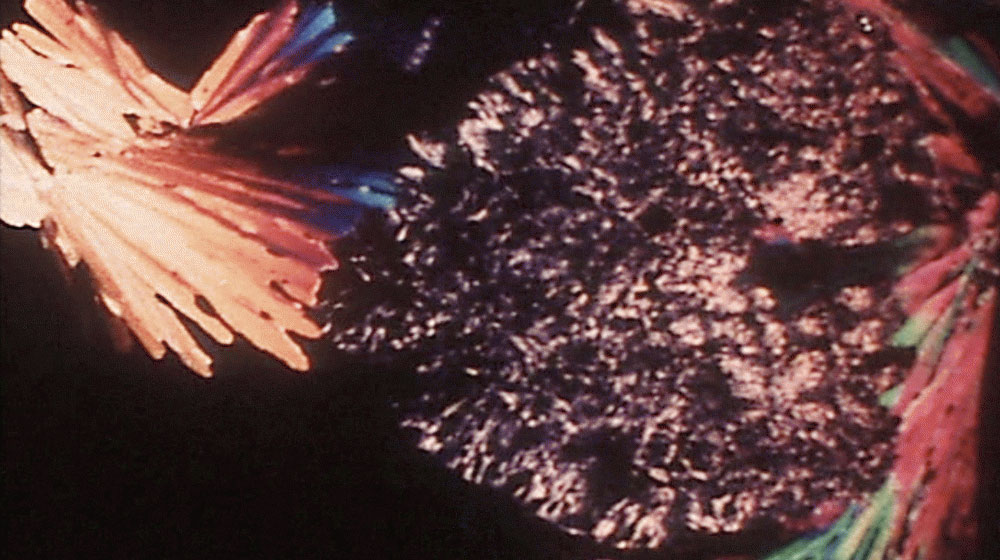

Before being defined as a form of entertainment, cinema was characterised by many of its early audiences, journalists and inventors as a medium for education. In The Kingdom of Shadows (1896), in which Maxim Gorky describes one of the first film screenings he attended, he refers, among other impressions, to the scientific importance of this invention which "could probably be applied to the general ends of science, that is, of bettering man's life and the developing of his mind". It's significant that the Russian writer should note these impressions not after seeing films such as Solar Eclipse (1900) or the First X-Ray Cinematograph Film Ever Taken (1897), frequent in the Victorian film programmes of the time[2], but various works by the Lumière brothers[3]. This fact serves as an excuse for us, in addition to "radically rethinking categories such as fiction, documentary and essay, [...] to access, on the one hand, an effective application of the etymological condition of documentary; that is, docere (teaching, transmission, education: a gesture which, taken to the extreme, means that any film can assume documentary [pedagogical] status) and, on the other hand, [...] support the scientific and pedagogical 'origins' (of the history) of cinema[4]".

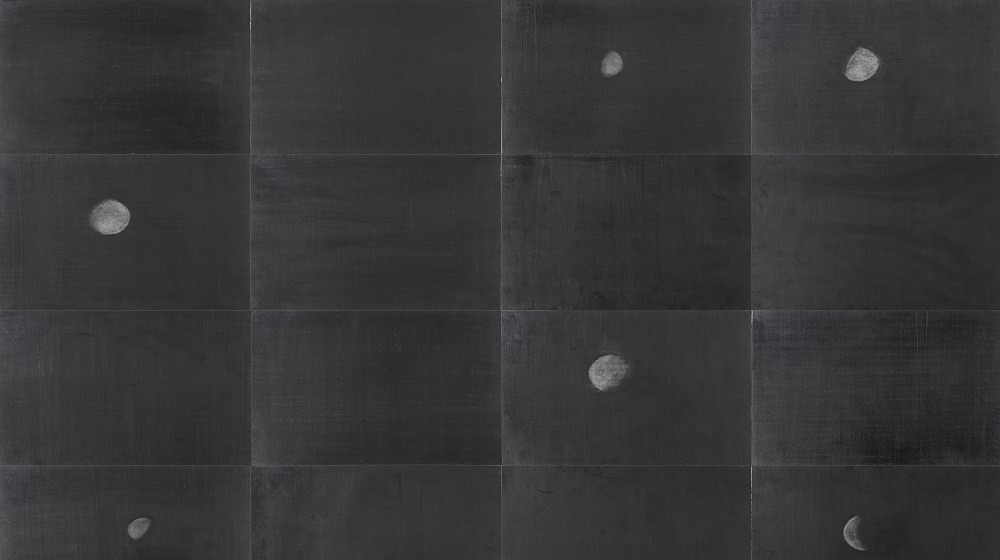

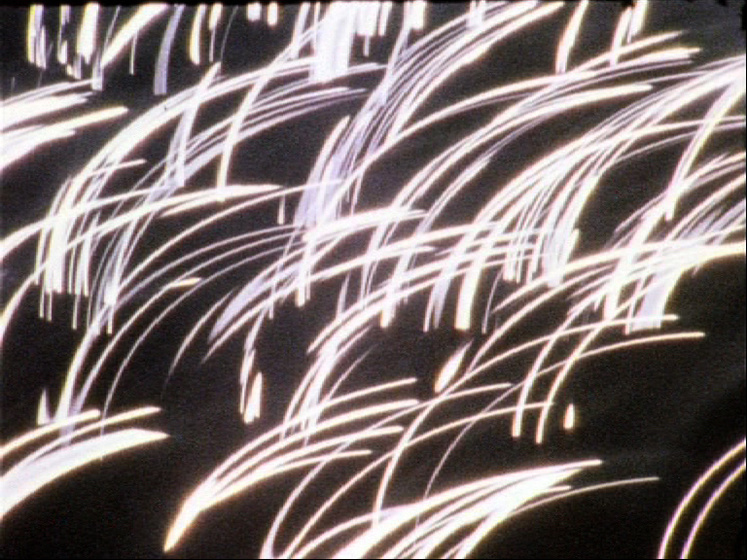

This scientific and educational vocation of early cinema, which later on became an entire genre with its own projection locations, was already present in the work of researchers such as Eadweard Muybridge and Étienne-Jules Marey. It's impossible to understand the natural history films made during the first few decades of the 20th century, such as The Acrobatic Fly (1910) or Percy Smith's The Birth of a Flower (1910), without taking into account such earlier chronophotographic experiments. In addition to being shown in cinemas, these popular science films, as well as others of a hygienist nature[5] produced by Pathé, Gaumont, Charles Urban and Edison, also started to be screened in other places: factories, schools, trade union centres, churches, museums and libraries, among other meeting places[6]. At that time, a large number of schools acquired film projectors and began to use films as a pedagogical tool[7], materialising the presentiment of Thomas Edison and Charles Pathé, who'd seen cinema as the school of the future that would replace textbooks and teachers[8]. Years later, José Val del Omar made identical assertions in his text Sentimiento de la pedagogía kinestésica (1932). Faced with the "antiquated education" of the time, this filmmaker from Granada believed that the technical processes of cinema, its capacity to retain and emit "documents torn from space and time", could create a new pedagogy, freeing it from the authoritarianism of the past and from methods based on textbooks[9].

Although "classroom films" emerged in the 1920s, it was not until the end of the Second World War that the showing of films in classrooms became commonplace and brought about a radical change in the way pupils engaged with knowledge, at least in the United States. This was partly due to the adoption of military training methods employed in the forces during the war, when films were used to teach various subjects such as map reading, artillery skills, disease prevention and so on. This led to the creation of a distribution circuit for educational films, in turn promoting the production of films, mostly in 16mm, that dealt with different fields of study,[10] as well as others with a more propagandist purpose, whose aim was to teach rules of conduct that would show young people how to be good citizens. Although these films were screened and seen by many, they have since been forgotten by film studies and history.

Teaching with film was certainly no easy task. In addition to technical skills, it also required complex decisions to be made, similar to those faced by a film programmer: selecting the films and establishing their order, determining the time in the class when the material selected should be shown, transforming the classroom into a cinema of sorts (darkening the space and finding a good location for the screen and projector), having a projectionist (often the teacher or a student), deciding whether to pause or repeat fragments and preparing the introduction and discussion[11]. As a result, pedagogical films not only taught people different subjects but also how cinema itself worked. However, schools were not only a place where films were screened, where the classroom lights were switched off to create a miniature cinema; schools were also represented in many films in which, conversely, cinema was transformed into a classroom.

The relationship between cinema and teaching is as old as cinema itself and has become confused with it. Cinema's technical developments have occurred in parallel to many changes in education, including the institution of state education. The image of education has been present in cinema since the early days of film, its places of education and their constitutive elements - such as blackboards, desks, books and other didactic material - acting as the stage, as well as certain films dramatising learning, creating conditions for its critical investigation. An example is provided by some early films, such as those shot by Mitchell & Kenyon in Blackburn following the approach taken by the Lumière brothers: Audley Range School (1904) and St Joseph's Scholars & St Matthew's Pupils (1905). In the endless movement of girls and boys crowding in and out of the schools, we can perceive changes in the educational system and the standardised, compulsory regime of primary education that had come into being at that time in England with the Balfour Act (1902) [12]. In addition to historical documents, these films, advertised as "Local Films for Local People", were also shown at fairs where pupils and teachers came to see themselves on screen, spectators who were also scrutinised by the English camera operators as they left the schools.

Let's look at other examples in which film has tackled the image of teaching, questioning the educational experience and established teaching model. The inauguration of a school in Germany allows Alexander Kluge to create a historical reflection on what teachers represent and to question the role of schools and their forms of education in Lehrer im Wandel (1963). Both in Kluge's film and in Mitchell & Kenyon's works, which portray the strictness of the Edwardian education system, and also in Ernesto, the character in Jean-Marie Straub and Daniele Huillet's En rachâchant (1982) who refuses to go to school, an attempt is made to show the stagnation of this institution. In contrast to this stagnation, Estampas (1932), by José Val del Omar, documents the work of the Misiones Pedagógicas or Pedagogical Missions, which eschewed the use of exercise books and blackboards for teaching, preferring projectors, record players, books and paintings transported by the missionaries from village to village. In this kind of itinerant school, in which the Granada filmmaker took part during the Second Republic, the aim was for instruction to be spontaneous and lively. The varied programme of activities included film screenings, sessions made up of documentaries, comical, educational and animated films, with a rural audience that was enthusiastic and amazed by the screen, so unfamiliar to them[13].

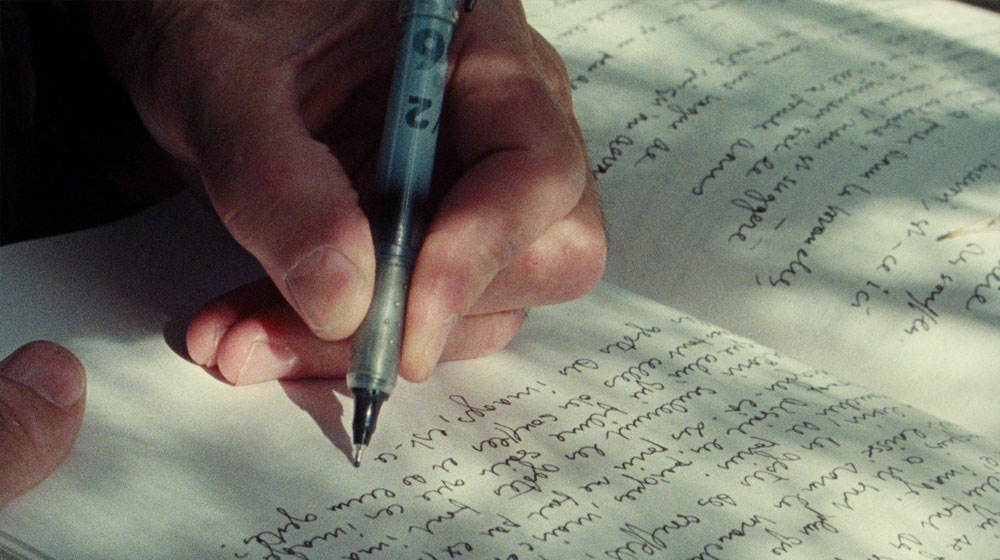

In addition to the open-air school of the Missions, enabling a certain permeability between school and the local community[14], a number of films have presented other alternative models of pedagogy. In Diario di un maestro (1972), Vittorio De Seta set out to create a new school inspired by the ideas of Célestin Freinet, in which the authoritarian relationship between teacher and pupils, syllabuses and textbooks is abolished, the teacher becoming merely a collaborator and the pupils the protagonists of the pedagogical process underway. Something similar also occurs in Peter Nestler's Aufsätze (1963), a film that shows the communal life of schoolchildren in a rural Swiss environment as described by the pupils themselves in their essays. On the other hand, Le Moindre Geste (1971) doesn't document a certain kind of education but transposes to film the cartography carried out by Fernand Deligny in his laboratory in the Cévennes. In this respect, the camera became an important tool for this educator, allowing him to create a system for transcribing the movements and gestures of autistic children, tracing the continual shifts and digressions without trying to represent them. With these minimal gestures, all previous film language, categories and forms and pedagogical methods are suspended[15]. All that remains is to learn "en rachâchant", as Ernesto says in Straub and Huillet's film[16], or through the infinite array of stories that precede sleep, as if their images could think, as seen in Harun Farocki's series for children Einschlafgeschichten (1977).

Celeste Araújo

[1] Frampton, Hollis (1971). "For a Metahistory of Film: Commonplace Notes and Hypotheses". In: Circles of Confusion, Rochester, N.Y., 1983, pp. 107-116.

[2] These films were accompanied by informative talks, the so-called film lectures, given both to the general public and to the scientific community which soon started using film as an instrument for research and education.

[3] The Departure from the Factory, The Baby's Breakfast, The Arrival of the Train, The Card Game and The Watering Can were some of the Lumière brothers' films, made in 1895, that Gorky saw screened at the Nizhny Novgorod film fair in 1986.

[4] Amorim, Miguel (2021). "Docência. Na verdade, os filmes não se fazem: refazem-se e/ou criticam-se". In: Diário do Minho, February.

[5] Such as the films related to the tuberculosis prevention campaign, for instance Langdon West's The Temple of Moloch (1914).

[6] See Lefebvre, Thierry (2012). "Esthétique spontanée du cinéma savant. Scientifiques anonymes 1912-1913". In: Collection Films. Paris: Éditions du Centre Pompidou, pp. 33-36.

[7] New technologies, optical devices (magic lanterns and stereoscopes) and different graphic material always formed part of the pedagogical resources of most schools in the United States. This educational practice was intensified by the cinema. In this respect, see Trees (1928), Eastman Teaching Films.

[8] See Peterson, Jennifer (2012). "Glimpses of Animal Life: Nature Films and the Emergence of Classroom Cinema. In: Learning with the Lights off. Oxford University Press.

[9] In addition to actively taking part in Pedagogical Missions, Val del Omar also developed a device called a Grafo-Omar to provide schools with a mini-cinema containing a projector, screen, films, slides and other graphic material. See Val del Omar, José (2010). "Proposición del aparato Grafo-Omar" and "Sentimiento de la pedagogía kinestésica". In: Escritos de técnica, Poética y Mística. Barcelona: Ediciones de La Central.

[10] History, geography, botany, geology, geology, zoology, bacteriology, genetics, public health, mental hygiene, aeronautics, metallurgy, surgery and agriculture, among many other subjects.

[11] See How to Use a Classroom Film? (1962)

[12] Years earlier, these children would have formed part of the ranks of factory workers, as we can see in some of the Factory Gate Films shot by the same camera operators.

[13] The audience's ecstatic response was decisive for Val de Omar and his (pedagogical) conception of cinema.

[14] This permeability between school and the local community is also present in Peter Nestler's Aufsätze, Vittorio De Seta's Diario di un maestro and Fernand Deligny's Le Moindre Geste.

[15] See Amorim, Miguel. K: EME (Kínema: enclave meridiano existencial), ou, Cinema (em) revolução permanente, ou Abecedário para uma cinemãeteca (fantasma) permanente – sem cinema não há filosofia, nem esta não se desmonta: mas também não se revela, nem se esconde, é tão só um episódio na história (da verdade) dos ecrãs (ou: o cinema pensa na, e pela, vez do olho, ou, o cinema pensa pelo olho ao projectar o mundo de um ecrã), ou, A não-reconciliação da fotofobia, ou, Vicitação do mundo pelo cinema, unpublished.

[16] In this film, the cineastes sum up the pedagogical endeavour present throughout their filmography: "the need to rethink everything we already know, to reteach what was already known but now forgotten". Zunzunegui, Santos (2007). "La mariposa y el crimen. A propósito del cinema de Jean-Marie Straub y Danièle Huillet". In: Archivos de la Filmoteca, no. 55, February, p. 103.