In Notes on the Cinematograph, Robert Bresson writes: "Today I was not present at a projection of images and sounds; I witnessed the visible and instantaneous action they were exerting on each other and their transformation. The bewitched reel". We can detect a thread running through cinematographic creation according to one of its most genuine experiences, waiting for this transformation on the very material of the film; bewitched, liberated or emancipated as a form independent from any other artistic medium and pre-verbal experience. A tradition whose nucleus could be Vampyr, where a light badly placed on the lens, accidentally resulting in a greyish shot, would reveal a style of film to Dreyer; and which would continue, in addition to Bresson, with another great filmmaker who influenced Mani Kaul, his maestro Ritwik Ghatak who, in 1966, started teaching at the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII), where his main disciples - Kumar Shahani, John Abraham and Kaul himself - gave rise to the so-called New Indian Cinema.

From Ghatak to Mani Kaul blossomed a beautiful path of Modernity in Indian cinema that was founded by Renoir and Rossellini on its very shores.. However, this path was later cut short or rarely travelled. In this century, Godard lamented the "international quality" that made all films - sub-Antonionis - look the same at festivals, while the path taken by Paradjanov had not been explored. Something similar can be perceived in the films of Mani Kaul, who takes the tradition of Bresson (particularly noticeable in his early films such as Uski Roti and Duvidha) and his commitment to film each shot as a whole, and from a single possible angle and lens, and ends up discovering his own cinematographic form. “The difference between the master and your imitation, the subtle difference, the exact distance/angle of the disparity, will lead you to understand something about yourself. The natural inability to imitate someone else perfectly leads to a realisation of our own inner and original strivings. All so-called ‘mistakes’ in following/imitating the master are the first cracks that will open out into a chasm that will differentiate his work from your own. Your imagination then becomes your own”.

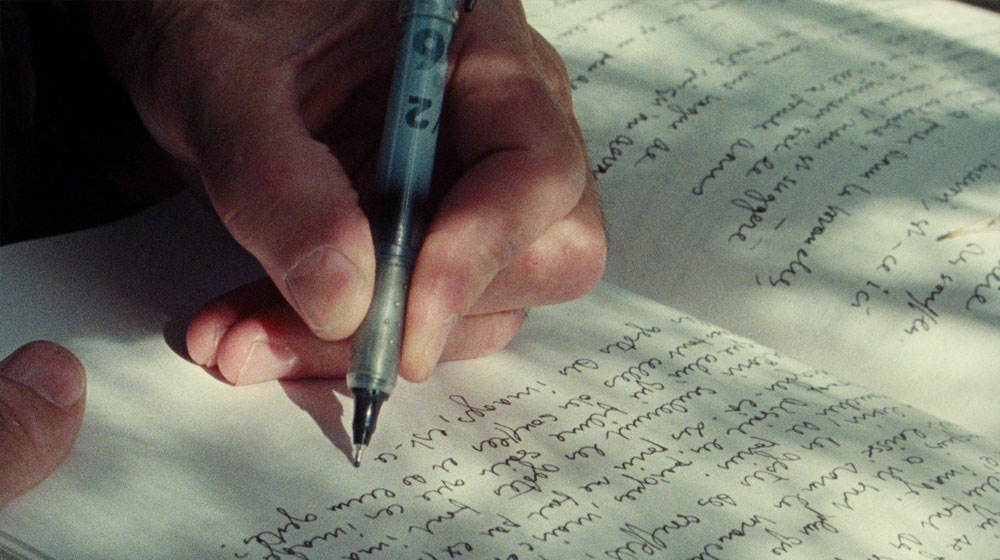

A retrospective of Mani Kaul makes it possible to see this progression- patient and uncompromising struggle towards that experience of transformation, the bewitched reel, which passes through the elimination of all residue, both literary and structural, and which culminates in Mati Manas. This is a three-pronged struggle against the threat or shadow of the verbal: the idea, the script, and for music without notation, a cinema without the written text; a struggle with oneself, or against the cultural remains and layers that limit, immobilise, atrophy and shackle. (“Today, although we’re very open to new relations or people politically or even industrially, I think the sensuality that binds us is still very old. Because the new sensuality has yet to mature (...). So, ultimately, at least for me, artistic activity is that which, in some way, attempts to alter this sensuality. It somehow tries to bring a new relationship into this sensuality and get rid of most of its dead matter. There’s a lot of dead matter sticking to this sensuality within us. It’s still there simply because we just can’t give it up”). And, lastly, a struggle to establish a pact and sustained relationship with the spectator, who is also invited to search for a new sensuality within him or herself, and to shake up and purify that dead material that also filters our point of view, and conditions us, exacerbates and distances us from what we’d be able to see. This is the main story of this collection of films by Mani Kaul, freed up from the narrative.

Uski Roti still starts from a short story, written by Mohan Rakesh in Hindi and shown in a non-linear way: a woman walks, every day, from her village in Punjab to bring her husband his lunch, a bus driver who is hardly ever home, until one day she misses the bus. The film reflects the temporary discomfort of her waiting and her anguish, the life of her mind. Kaul only used two lenses throughout the film: a 28mm and 135mm lens. At first the long focal length brings us closer to the most introspective and dreamy states, while the wide angle shows the actions in depth of field, in a more realistic way; but when the film enters the woman’s head, by means of fantasy and flashbacks, the lenses are reversed and the spectator becomes uncertain as to whether what the woman is seeing forms part of the fantasy or past, real life or imaginary.

Mani Kaul sums up the poetic, musical and plastic approach to his work: “When I made Uski Roti, I wanted to completely destroy any semblance of a realistic development so I could construct the film almost like a painter. In fact, I’ve been a painter and a musician. I could make a painting where the brush stroke is completely subservient to the figure, which is what narrative is, in a film. But you can also paint stroke by stroke, so that both the figure and the strokes are equal. I constructed Uski Roti shot by shot, in this second way, so that the ‘figure’ of the narrative is almost formless in realistic terms. All the cuts are delayed, though sometimes there’s a preference for a generally uniform rhythm, when the film is a projection of the woman’s fantasies”.

Neither Uski Roti nor his next film, Ashad Ka Ek Din, were ever released in cinemas. In 1972, Kaul was therefore desperate to work. The famous painter Akbar Padasee helped him by lending him a 16mm Bolex camera with a 16/86mm Switar lens and several reels of very slow Kodachrome - 25 ASA (daytime film) and 40 ASA (tungsten) - which he used to film Duvidha, his third feature and his first colour film, based on a folk tale by Vijaydan Detha. Mahajan, who’d been in charge of Uski Roti’s photography, refused to commit to Duvidha when he learned that it was to be shot with a Bolex under amateur conditions. Kaul only had four 1,000-watt lights, normally used for filming news stories. The reflectors were handmade and he’d taught the villagers to hold them, as the voltage in rural Rajasthan was very low. Finally, he decided to collaborate with Navroze Contractor, who had only worked on still photography until then, reassuring him and explaining that, for him, the moving image was just an extension of photography. As there was no money to work on the sound, Kaul reduced the dialogues to a minimum, with the idea of resorting to the aesthetic of silent films.

Duvidha aroused his interest in popular artistic practices and non-urban folklore, whilst at the same time leading him to further his experience of using real literature to get rid of the script. At this point in his work, and in relation to the camera and the process of filming, he felt the need to construct his films by placing himself in time: “You have to learn to hold the camera with your own rhythm and not just have an idea in your head and try to illustrate that idea. You have to understand that, even when a cameraman is physically shooting the film. We all create differently, precisely because each person’s body moves differently. Your movements are like a dance (...). I sincerely believe I could make a film now without looking through the camera. In fact, I have a project in mind where I won’t let my cameraman look through the camera. Looking through the camera was obviously important to me when I made Uski Roti, because at that time I was thinking about how space was organised. Since the European Renaissance we’ve been used to thinking that organising space, and especially sacred space like a church or a temple, is what creates a sense of attention and therefore time. But now I believe that I should actually place myself in time and in a certain quality of attention, and allow the space to become whatever it becomes. It doesn’t interest me anymore to compose my shots, to frame them in some way. I want to place myself in a particular sense of time and let space be or grow. Nothing can go wrong, I know that, nothing can go wrong”.

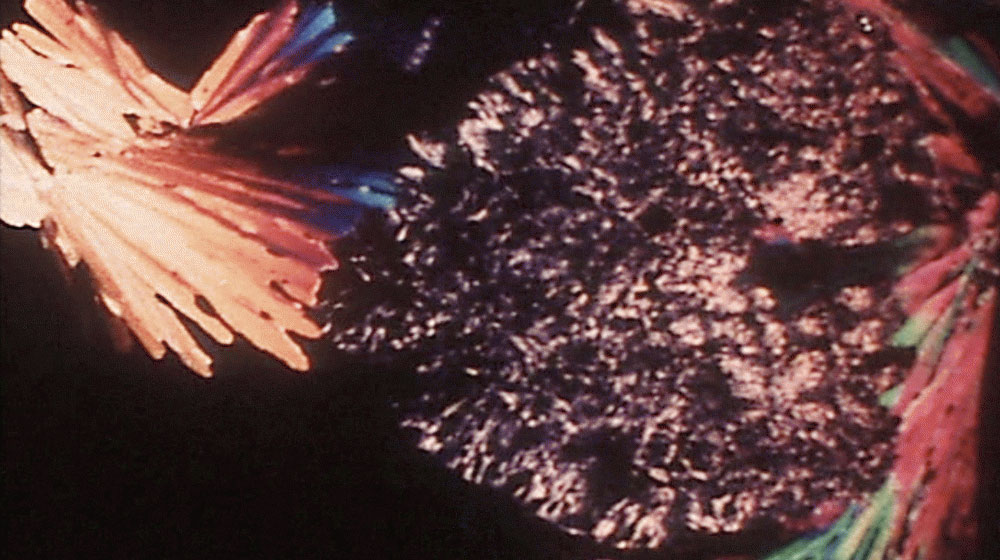

Kaul assembles his films just as music is composed. By moving the shots along the timeline, they find their place based on rhythm or mood. In Dhrupad it’s not the music that is represented but the idea. The portrait of the brothers Zia Moiuddin (rudra veena player) and Fariduddin Dagar (vocalist), with whom the filmmaker studied, is not only a historical study and a document of their performances but also an experiment with time based on the construction of fractals and mise en abyme. Unlike jazz, raga is improvisation made up of a single scale, although each scale may contain three or four different ragas. In Dhrupad, the oldest form of Hindustani classical music known to us, each raga is sung or performed in sections of approximately one and a half hours, day or night. As Kaul shows in his film, ragas follow their own natural cycles, associated with waking or sleeping. Ascending and descending tones travel between the dissonant zones, without fitting into existing notational systems. Dhrupad students must discover the relationship between the number of rhythms and the number of words or letters that join with the progressive rhythms of each specific taal, thereby forming a cycle. That’s why this tradition can only be passed on orally. The different types of silence are beyond tonal expression and no instrument can achieve the timbre of the malleable voice. The singing is intuitive, grammatically correct, perfectly subjective. Interpretation is based on attention while listening, speaking, seeing, feeling or touching.

In his interview with Serge Daney, Kaul wondered what the camera or recorder can express, and not so much the filmmaker. In transposing music to the form of film, each shot is also thought of as an orchestration of space. The relationship between music and architecture (the corridors of Gwalior Fort, the geometric structures that defy perspective at the Jantar Mantar astronomical observatory) involves assembling colours and producing volume. In one of his aphorisms, Mani Kaul wrote that movement is guided by light. By simply joining dots or following the lines that cross the tactile edges, the camera seeks to free itself from the tyranny of the eye.

Just like painting stroke by stroke, Kaul films shot by shot so that both the figure and the strokes are the same. In Mati Manas, each new event blurs and transforms the memory of the previous one; each shot looks like the first. The pieces are secretly re-launched, changing dimension. Time doesn’t repeat itself but returns, opens up. Pottery is shown in books such as the one by Pupul Jaykar, or in the showcases of museums housing icons of heritage, pieces from the Indus Valley, some of the oldest examples of Indian civilisation. However, wondering how archaeology may have been perceived at the time of its creation, the filmmaker rejects the idea of producing a catalogue. For Kaul, pottery is a pool of existence that arouses from all eras. Showing the technique and social history of an image as archaic as ever, glimpsing the state of mind in which each object was made means evoking this using angles, contrast and placement. Filming is weaving textures, things and beings. Throughout the film, each mould, figure and statue looks like the same one and also a different one, both at the same time. Working the wet clay gradually makes a form emerge, that is the form of the film itself.

Travelling on a tour bus through central, southern and eastern India with a team of twenty people, the fragmented scenes in Mati Manas come together as if everything was happening in one location. The many different geographies, realities, narratives and timelines show us that the immobile only becomes available within a flow. We know that clay and earth are inseparable elements of the imaginary. Like alchemy, the camera slides before our eyes, opening up passages in which image becomes words, solar and lunar words that seem to be heard for the first time and yet have been heard thousands of times. These are the myths associated with pottery: the ocean of rivers of legends, the tale of the witch Gangli, the Mesopotamian legend of Gilgamesh and Enkidu or that of Parashuram, the icon of Kala-Gora or the story of the mother cat who sheltered her young in fired clay jars. Fables that refer to the origins of patriarchy or the transition from a pastoral to an agrarian system, retained in their original form and interwoven with fictional sequences. Stories told by the potters themselves or recalled by the three historians, all filmed from the back or the side, based on the idea of an unconnected figure: there’s no centre in the body, a face isn’t more important than a hand, there’s no difference between a face and a tree. "You cannot express an emotion through a gesture. Emotion can express itself in a gesture".

Francisco Algarín Navarro and Gonzalo de Lucas