The filmography of short films by the Brazilian filmmaker Aloysio Raulino between 1970 and 1986 is one of the most valuable repositories of cinematic thought translated into image and sound on record, insofar as it represents an emphatic attack on the hegemonic documentary tradition. Between Lacrimosa (1970) and Inventário da Rapina (1986), Raulino forged a path from the edge, walking steadily with his camera in hand towards those on the margins of society, whilst he also questioned the gesture of filming a people, in each shot and in the editing.

In 1978, the filmmaker Arthur Omar published a decisive text in Brazil, "O antidocumentário, provisoriamente" [The anti-documentary, provisionally],[1] in which he attacked the dominant documentary: "That is the secret of the documentary (forced by its affiliation with the narrative cinema of fiction): to offer its object as a spectacle. The interested spectator suffers from the illusion of knowing. Of mastering, through knowledge, what the film is showing". Albeit not translated into words, the cinema that Aloysio Raulino had been practising since 1970 was already a radical formulation of what Omar proposed as an antidote: the practice of anti-documentaries, in which each film would incorporate, into its own form, the opacity, the mediations, the questioning of how to film.

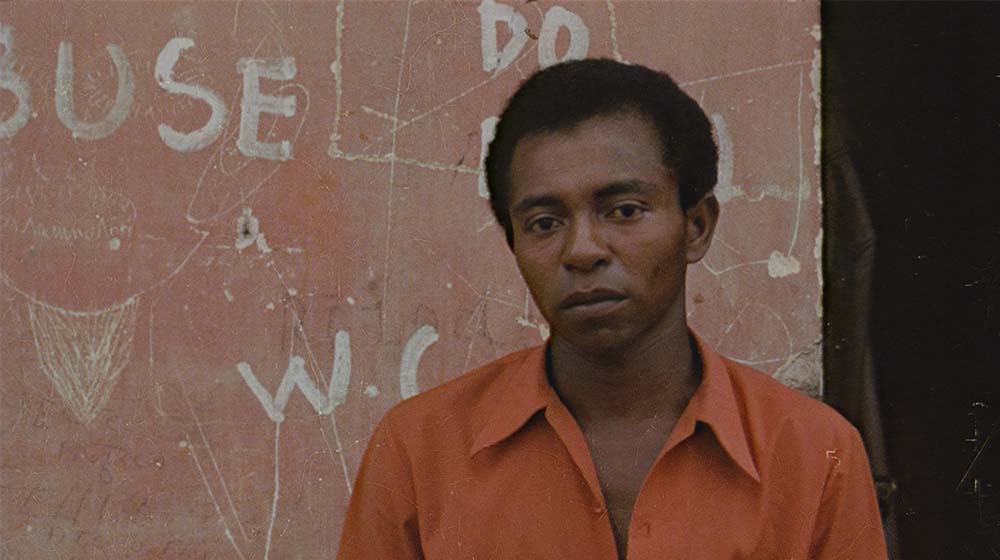

Lacrimosa, co-directed with Luna Alkalay when they were still at university, is the result of an experience that affected him deeply: his participation in the historic second meeting of Latin American filmmakers in Viña del Mar, in November 1969, when he encountered the films of Fernando Birri, Jorge Sanjinés and Fernando Solanas. Raulino says "it was my first organised response, as a filmmaker, as a human being, perhaps as a living force, to this experience" (RAULINO, 1980, p. 58).[2] With their eyes illuminated by this contact with the most eminently incendiary fringe of Latin American cinema, Raulino and Alkalay set off in a car towards the outskirts of the great metropolis. "An avenue has recently been opened in São Paulo. It forces us to see the city from the inside" says the opening title. The shaky camera films the rainy margins of the great avenue, the ruins of a country destroyed by a civil-military dictatorship in its most repressive phase, while fragments of milongas and other popular Argentinean songs can be heard on the soundtrack. All at once, suddenly, the film breaks in the middle (as will happen so many other times in Raulino's filmography): the car stops and the filmmaker sets off, camera in hand, towards the interior of a favela. "Rubbish is the only means of survival", says the title. What follows is a clash between the camera and the faces of the inhabitants of this post-apocalyptic landscape. While Mozart's Requiem is punctuated by long silences on the soundtrack, the two senses of "duelo" in Spanish intertwine, namely mourning and a duel: the sense of mourning for a kidnapped country combines with the sense of a battle for attention, a duel between a dance and a fight, transforming each shot into permanent instability. Raulino doesn't film in order to portray misery but so that miserable people can return the incisive gaze on the front axis of the camera, swallowing us into the centre of this duel between the person filming and the person being filmed. Raulino's cinema is a clandestine, improbable bridge between the utopian ambitions of Cinema Novo - to discover an invisible country, to reveal its entrails, to invent a people - and the exasperation of Cinema Marginal - faced with a country suffocated by state terrorism, to drown in rubbish and move on to aggression.

Raulino's camera pursues the faces of the marginalised but always with the awareness that it's not possible to film them without questioning, in each shot, the cinematographic gesture itself. In Jardim Nova Bahia (1971), the portrait of a car washer and the north-eastern community in São Paulo bifurcates into a pioneering experiment: passing the camera around so that Deutrudes Carlos da Rocha can film himself and his friends on a trip to Santos. In Deutrudes' framing, the viewer seems invited to find evidence of a historically marked body. But then "Strawberry Fields Forever" begins to play on the cloudy beach, and what seemed to be a well-intentioned exercise in the transfer of power changes shape: "misunderstanding all you see", authorship is blurred and the question of who these images belong to is impossible to answer. We're far from demagoguery: the film is not a transfer of ownership but the radical becoming of an improper cinema in which the very ideas of authorship and ownership become impossible to decide.

Teremos Infância (1974) begins as a portrait of Arnulfo Silva, a man who wanders the streets of São Paulo and describes himself as "the most erudite physicist who guides the universal peace of mind". Between images of the city and his face in the foreground, Arnulfo recounts the bitterness of his miserable childhood when, suddenly, Raulino's camera reframes to reveal two children who live on the street and are closely watching the filming, right next to the sound recorder. Like a sort of cinematic miracle, Arnulfo's childhood memories materialise out of shot. From then on the film, split in the middle, devotes itself to accompanying these children, drifting through the city in a series of failed interactions. Incisive movements towards the opaque gaze of the children, attempts to extract something from them in the soundtrack ("But say what?" / "Invent a story!" / "But I don't know how to say anything..."), all the fissures, all the gaps in the relationship between the person filming and the people being filmed are assumed by the editing as the real interest of the film. Teremos Infância isn't a documentary about a miserable childhood but an essayistic amassing of broken mirrors.

In the prologue to O Tigre e a Gazela (1976), the screen is taken over by an enigmatic image: a pair of hands cleaning a pair of fogged glasses, raised in front of a whiteness that doesn't allow us to distinguish anything beyond the opaque glass. While we listen to a quote from Frantz Fanon on the soundtrack ("The intellectual abandons calculation, unwonted silences, ulterior motives, reticence and secrecy as he integrates himself into the people"), the film interposes two other mediations - in addition to that of the camera - between the spectator and the world, in a material investigation into the nature of the figurative gesture. The relationship between the intellectual and the people, analysed by Fanon, will be the subterranean leitmotif of O Tigre e a Gazela. Throughout the film, Aloysio Raulino creates two gestures: on the one hand, Fanon's immersion in the people translates here into a camera set-up for an open-air encounter with a series of popular characters who've traversed the history of the documentary, migrants at a train station, drunks and vagabonds, dancers at a samba school; on the other hand, this documentary drift is constantly set up with moments of essayistic meditation in which the filmmaker takes diverse fragments of music and text and projects them onto the images, in a constant dialectic. The voracious use of quotations ranges from Fanon and Aimé Césaire to Lima Barreto, and the soundtrack features pieces from Joseph Haydn to Luiz Melodia and Milton Nascimento. Raulino knows he can't speak for the people nor form a simple alliance, so he decides to work on the breadth of this gap. "Oh, my body, make of me always a man who questions", says Fanon's sparkling phrase that closes O Tigre e a Gazela. This is the heart of the film's figurative invention: to question - the people, cinema - but to question with the body, in a permanent battle between critical intellectual distance and corporeal immersion in the world.

O Porto de Santos (1978) is a cartographic drift through the most important port city in Brazil, in which Raulino's camera traces a kind of upside-down map: what we see are not the tourist spots and the economic strength of the port but the marginal areas, the daytime struggles of the dockers and the night-time work of the prostitutes. In this travelogue on foot, the figurative arc will also be a story of the gradual conquest of gazes, of the growing trust between the person who films and those being filmed - a relationship, however, that is never free from confrontation. The apex of this turmoil occurs when, in one of the bars on the quayside, Raulino composes a group portrait in which a group of women stand out, laughing, conversing, looking confidently towards the camera. That's when a woman's voice begins to take over the soundtrack, projecting itself over the music and the noise from the bar: "Could you make a film about our lives?" In the voice of Santos's prostitutes, the murmur of the people becomes, for a moment, intelligible, penetrating the soundtrack to demand another film. Whereas, in Teremos Infância, it was Raulino who questioned the children in search of stories, here it's these women who challenge cinema, expressing their desire for representation. A film about a split city becomes a broken film, torn from within by a figurative energy it's unable to control.

Inventário da Rapina (1986) is a film-limit. For the first time in Raulino's cinema, the drifting through the city is accompanied by the camera turning towards the filmmaker himself and his family. Its solipsism and insularity, so rare in Raulino's work, are the realisation that perhaps it was no longer possible, at least in Brazil at the time, to acknowledge the rebellion of the people without recognising the solitude of the poet. In the same movement, however, there are, for the last time, the gazes of children, with their eyes blindfolded but also frank, determined. The camera that turns for the first time towards the filmmaker himself is the same one that sets off, once again, towards the street. Once again Raulino's cinema refuses to acknowledge the disaster of the disintegration of the people without seeing the promise of a people yet to come. Once again cinema tears itself apart and explodes into a thousand pieces, but Raulino insists on walking on its rubble.

In a text by Guy Hennebelle and Raphael Bassan from 1980, published in a dossier of the magazine CinémAction devoted to the "two avant-gardes" - the "white" (experimental) and the "red" (militant) - we find confirmation of an idea that's extremely useful for thinking about Raulino's cinema: "In Latin America, the gap between 'militant cinema' and 'experimental cinema' is not as clear, nor of the same nature, as in most industrialised countries" (HENNEBELLE; BASSAN, 1980, p. 190).[3] From the south, the pretended division between experimental and militant cinema needs to be rethought, and Raulino's cinema is a privileged territory to reflect on this. His political commitment to the figuration of the people has always been inseparable from a profound experimental search that has transformed the parameters of the very possibility of cinematic figuration.

By Victor Guimarães

[1] OMAR, Arthur. "El antidocumental, provisionalmente". In: PARANAGUÁ, Paulo Antonio (ed.). Cine Documental en América Latina. Madrid: Ediciones Cátedra, 2003, p. 468-471.

[2] RAULINO, Aloysio. "Depoimento". In: ROBERTO DE SOUZA, Carlos. SAVIETTO, Tânia. (orgs.). 30 anos do cinema paulista - Cadernos da Cinemateca 4. São Paulo: Fundação Cinemateca Brasileira, 1980. p. 55-62.

[3] HENNEBELLE, Guy and BASSAN, Raphaël. "Les deux avant-gardes. CinémAction, no. 10-11, 1980, p. 5-7.