From 1958 and throughout the 1960s, António Campos made more than twenty-five films almost on his own, without the help of a crew, some of which were shown at film clubs and amateur film festivals. At the same time, research by ethnographers, writers and artists was beginning to develop in Portugal, focusing on traditional crafts, forms of music, speech modulations and popular rites in rural environments. Campos approached ethnography in the period beginning with Vilarinho das Furnas (1971), seeing as a crossroads between heterogeneous methodologies. His documentaries tend to mix together different registers such as geographical and historical description, interviews, reconstitution and the recording of live actions, as well as making use of different materials such as photographs, drawings, maps, poems, commentaries, stories and different types of text.

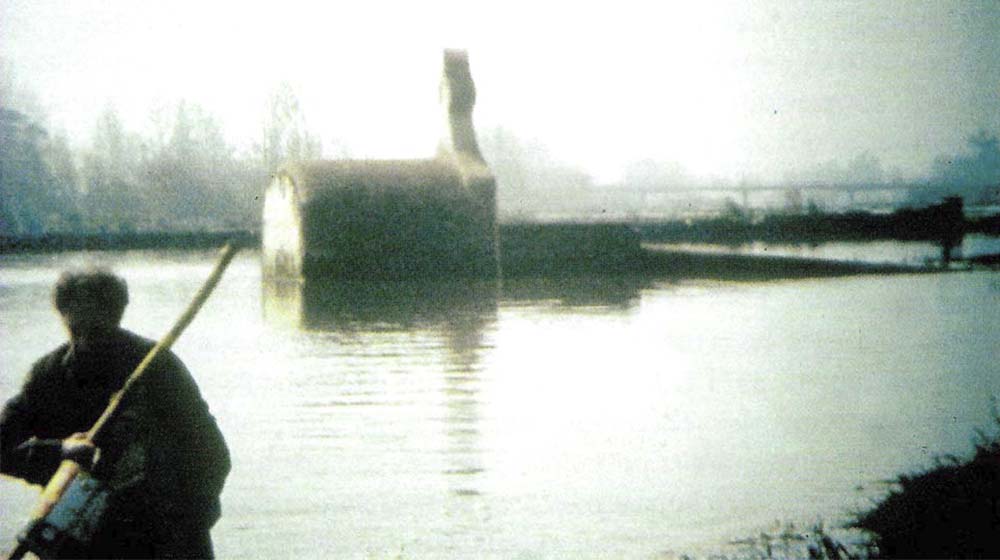

His first feature film, Vilarinho das Furnas, provides a portrait of an ancient village organised based on a system of community self-government, filmed by Campos in the last year before its demise. The inhabitants of Vilarinho were in conflict with a hydroelectric company that wanted to build a reservoir whose dam would end up flooding the village. Based on the book of the same name by the ethnologist Jorge Dias, Campos spent eighteen months in the village filming the daily activities of the villagers, alternating domestic chores with work in the fields and mountains. In addition to the daily work, Campos was also able to record several community meetings, some of them particularly tense, as well as the liturgy of the religious processions that punctuate the film. Cyclically assuming the role of narrator, one of the villagers recounts how Vilarinho was first set up and explains in detail the workings of the village council (participatory procedures, laws and penalties), as well as the regulation of grazing areas and irrigation and cultivation systems. He also introduces other topics, such as the organisation of the festivities and the ritual pig slaughter, as well as revealing certain conflicts such as the visit by the civil governor on the occasion of the floods caused by the dam and the clashes arising from the budgets to maintain the chapel. In the film, recordings of their words alternate with the direct recording of conversations and discussions among other residents of Vilarinho. Except for occasional expressive disruptions, the images and soundtrack complement each other beyond description or illustration. They present the watershed moment faced by the village, reveal the different ways in which actions relate to each other, incorporate the tensions within the community and pass on the stories or personal situations with their corresponding digressions. But they also refocus all of this around a specific theme: the decline, in its various aspects, of the organisational system of Vilarinho, aggravated by the threat posed by the construction of the reservoir.

After spending time in Vilarinho, in October 1972 Campos settled in Rio de Onor, where he lived for eleven months with the inhabitants of this village, exemplary in preserving its centuries-old agro-pastoral laws. Once again following in the footsteps of Jorge Dias, who also made a monograph on this frontier town, Campos filmed Rio de Onor in the last months of the Estado Novo regime. However, the precepts that had regulated community life for centuries were gradually transformed over the two decades that separated the book by Dias from the film by Campos. The village suffered successive waves of its inhabitants emigrating, with the consequent ageing of the population, the incorporation of children and women into agricultural work previously reserved for men, and the exemption of small landowners from traditional laws. The film is determined by this demographic, economic and cultural change, to a certain extent latent in the images but constantly manifested in the words of villagers, whose voices completely guide the film - hence its title: Falamos de Rio de Onor (Talking about Rio de Onor) (1974). As in Vilarinho das Furnas, the sequences are based on mutually complementary relations between image and sound but this film doesn't contrast a montage of anonymous voices with a voiceover. On the contrary, the speaking is multiplied. Campos tends to have as many narrators as sequences and, on occasions, to film the people speaking with minimal mise-en-scène that acts as a counterpoint to the documentary approach. In parallel to the proliferation of personal statements, the film also deploys a variety of cinematographic registers that make the anthropological portrait of the village more complex. Among the different strategies used, Campos unusually distances figures and their background in circumstantial conversations between villagers; he films a sermon uninterruptedly, in a fixed shot with live sound; he uses a shot/reverse shot to portray a child witnessing the birth of a calf, emphasised with dramatic music; in several sequences he develops the research carried out by an anthropologist from Lisbon as an elliptical fiction; and from time to time he alternates the soft and intense colours of Ektachrome film with the ageing effect of sepia.

In 1975, Campos began filming Gente da Praia da Vieira in the region where he was born, for the first time with a professional crew. Following the trail of the fishing communities of Vieira de Leiria who, faced with the harsh winters, had migrated to Escaroupim, a village on the banks of the Tagus River, the film uncovers a series of analogies between the political, social and cultural situations of both populations. In Escaroupim it's the children who present, on the soundtrack, the themes related to the past and present of the village (such as its history, its architecture and the changes in the living and working conditions of the fishermen and peasants). On the other hand, in Vieira de Leiria, Campos uses some scenes from two of his fictional films made years earlier in the area, both to illustrate the historical description of the region (Um Tesoiro [1958]) and to examine local emigration via a reunion with its actors (A Invenção do Amor [1965]). One of these, Quiné, in collaboration with the Escaroupim theatre company, would be in charge of staging the recreation of the fishermen's housing conflicts. These scenes are interspersed with everyday life in the village and an interview with one of the landowners. The ideas of the young people who oppose maintaining the unhealthy fishermen's huts in Vieira de Leiria are confronted with the renovation proposals of an architect for whom the destruction of these traditional houses is a crime against historical heritage. For Campos, just as conflicts are best understood by juxtaposing the different opposing discourses, the reality of these two locations can be grasped by producing a collage composed of fragments of films, interviews, essays, observational recordings and theatrical recreations.

Three years later, in his first fictional feature-length film, Campos takes as his starting point two short stories by António Passos Coelho, working with both professional actors and local people. Histórias Selvagens (1978) focuses on the life of a couple of tenant farmers from Montemor-o-Velho who, now elderly, are evicted from the farm they've always worked on and forced to move to the unhealthy kitchen assigned to them by the landowner. Although in this case he's focusing on the lives of these particular people and not on a community, Campos doesn't use the village merely as a set; introduced by maps and drawings that provide a geographical and historical description, fiction is contrasted with the past and present of the village. Even so, what is substantial in Histórias Selvagens is not the blurring of documentary and fiction but the unpredictable variation between different registers of filming, acting and editing, both documentary (didactic narration, direct cinema, descriptive preciosity) and fiction (natural or distanced acting, austere or sensual staging, alternating, in the same scene, between realistic and irrational dialogue). The film also does away with a coherent timeline, jumping throughout the film between the protagonists as an adult couple - taking care of the land and their family - and as a lonely, elderly couple, materially and emotionally dispossessed. Histórias Selvagens is a film made up of abrupt cuts between different levels of narration and representation. If, in Campos's films, we can appreciate a unity in variation, this is because, for him, nature was never peaceful. Reality is seen as a construct that contains all these discordant discourses within itself.

By Francisco Algarín Navarro and Carlos Saldaña