-

I am thought

‘It is wrong to say: I think. One ought to say: I am thought’. Jean Rouch discovered Rimbaud at school. Later on, he recognised the difference between moi and je and, in creating a simulating narrative, a simulation of narrative, he once again encountered that ‘I is another’. Truthful narrative had been thus deposed. The form of identity of I=I (or its degenerated form they=they) was no longer valid. So it was Deleuze who saw the filmmaker-other in Rouch: his was a free, indirect discourse; he would take real autonomous people as mediators. ‘A black man acts as a black man through white people; and, in these, the white man finds the possibility to become black’ (Moi, un noir). Rouch was like a chameleon: it was said he used to take on the same colour as the place he was in at the time.

In 1941-1942, in Niger, Rouch met a Sorko fisherman called Damouré Zika. Distancing himself from the French elite, Damouré introduced him to the circle of fishermen. Rouch returned to Niger in 1946-1947; this time not as an engineer but as an anthropologist. There he met Lam Ibrahima Dia, a Fulani shepherd, and met up once again with Damouré. Together they went down the Niger in a canoe and, shortly afterwards, he filmed Damouré for the very first time. The young fisherman, when he saw himself in Chasse à l’hippopotame playing with a baby hippopotamus, suggested that Rouch should ‘invent a story, make a real film’. That was how Damouré became Rouch’s collaborator in Les maîtres fous and Mammy Water and, together with Lam, he became an actor, chauffeur, technician, friend and creator of a fictional process in which the characters gradually evolved. Together with Illo Gaoudel, a Bozo fisherman, they invented the serial: Jaguar, Petit à petit, Cocorico Monsieur Poulet, Babatou, les trois conseils, Madame L’Eau and Moi fatigué debout, moi couché (Tallou Mouzourane took the place of Illo in the last four of these films). Rouch would declare that ‘All the films I make are always Jaguar’.

Three faces, three temperaments, three ethnic races. In Petit à petit, Damouré and Lam were even editing consultants (Rouch had set up an improvised projection room and mixing studio at the Musée de l’Homme, where he would show the rushes as he shot the film) and, together with Illo (as well as the assistant Moustapha, the secretary Albora, helpers Moussa and Idrissa and the gofer Tallou), the rich partners from the fictitious import-export firm from the times of Jaguar, “Petit à petit”. Damouré had announced to Rouch that he was going to carry out an internship on the transition of African languages in Paris under the auspices of UNESCO, and Rouch responded with the proposal to film the continuation of Jaguar. Without pen or paper, Damouré and Rouch invented the story in a single night. In two days the fictitious office in Ayourou had been built and the prologue of Petit à petit was filmed, together with the real journey made by Damouré: when he got off the plane, when he discovered the Torre Eiffel from the Trocadéro and when he sent the first postcard. From then on, Damouré went around the city on his own during the 3-4 months his internship lasted, starting his explorer diary with the promise of writing up more precise reports later.

Three African masks, three harlequins, three brighellas. Based on the initial plot, the characters created a large-scale commedia dell’arte supplemented by gesture, action and the filmmaker’s improvised mise en scène. Their burlesque language was progressively perfected as they got to know each other better. It was not the picaresque of the comic related to the situation or characters; their “acrobatic gymnastics” arose from a superior type of friendship, from a savoir vivre, from a joviality in which truth emerged from laughter, from a huge joke. Their transition between states did not reflect reality but actually provoked it, created it, as in those fictitious images, with all their details, filmed by Eisenstein and from which, according to Rouch, Mexican life emerged. Repeating their roles from film to film, the person would undergo a metamorphosis: the actors seemed to exchange their skins for those of the characters; the proteiform identities appeared inseparable in their development. But none of them was, in life, what they were in the story: they weren’t playing themselves in front of the camera and microphone but neither did they entirely stop being themselves, since they were perceived and imagined and became others (Rouch compared this gap between a character and its personification on screen with cinema trance). First becoming established as real, never as fictional, the characters would confirm their inevitable fiction as potential and not as a model. In film, the art of the lookalike, life is lived at the limits of fabricating fiction. A character becomes real the more it has been invented; it is the “producer of truth”, as Deleuze says. The smallest incident is potentially false, since Rouch’s filmmaking is not so much cinema of the truth but the truth of cinema.

In the soundtrack for Jaguar, Rouch mixed the original conversations filmed in 1957 with the actors’ commentary, recorded a posteriori during the projection, when they were shown the images edited in 1967. Both the voices and the recording procedures had changed in that duplicated interval. In some scenes of Petit à petit, the a posteriori commentary by Damouré had been transformed into an inner voice that sometimes took the form of a monologue (a kind of extension of the notes in his diary) while at other times it was like an imaginary dialogue, such as when Lam, from Africa, answers him while he’s walking through the woods. It’s in these silent scenes when the characters reveal themselves through fantasy. When Rouch edited the images evoked by Safi about her country and cannibalism, the word became a “nascent state”, a chain reaction capable of upsetting the characters and creating enigmas, like the responses that are uttered but don’t seem to lead anywhere; like the moments of doubt when someone suddenly joins or leaves the twists and turns of a conversation. It would be useless to write scripts or dialogues for a society whose cohesion was orally based: for Rouch it was enough to give in to improvisation, the art of logos and gesture, to the natural poetry of the wordplay in the “broken French” of Damouré or Lam (Creole African languages were in full creative development). Only long takes could provide the necessary amount of time to express himself; dialogues emerged from the preceding reply, at a walking pace.

Rouch’s cinema is not more truthful than reality but it’s as truthful as fiction. The very process of creating leads to doubts. Did Rouch prompt the words repeated by Lam and Damouré? Maxime Scheinfeigel wonders about this complex intrafilm device: on the one hand, miserabilism was avoided by resorting to the power and money with which an anthropologist would travel around Africa. On the other hand, the aim was to transcend the caricature of the white ethnologist parodied by the black fictitious ethnologist (Rouch himself? The identity of the caricature artist was also unknown). Damouré not only studied French geography, sociology and psychology as an alter ego of the cineaste but also as his pro-filmic and intradiegetic double. This was a new character for cinema because, as pointed out by Scheinfeigel, in Petit à petit the other is no longer the African who comes from afar but our fellow citizens, the Parisian tribe. When the subject that is doing the looking is new, then a new object is looked at (such as the Somba people in Jaguar).

The other is not seen objectively nor does it see subjectively, it produces the other. It’s the disruptive role of the observer by definition (the foreign eye sees things not perceived by the local eye). If the ethnologist is so often the one who extracts general theories from particular analyses, and if anthropology is, as Rouch believed, the “eldest child” of colonialism, only if he invited African ethnologists to study his own tribe could an exchange come about with those who, previously, had solely been the object. In Petit à petit, Damouré’s anthropologist is not only an operator of fiction that contains all the previous images; the reversal of perspective is also subjected to schematised satire. Taking up Ousmane Sembène’s objection, Rouch seemed to encourage Damouré to treat the Parisian passers-by almost as if they were insects. On the one hand, the myth of the Western man was busted for someone who had only known France through a few postcards; on the other, since shared anthropology does not allow stolen secrets, as soon as Damouré’s impressions were written down, they had to be shown. The prisoner river, the cows-hippopotamus or electrocuted chickens astonish Damouré almost as much as he is scandalised by the physical features of the French, their lack of courtesy or the fact that the young women wear miniskirts. But, in summary, the scene when measurements are taken, Scheinfeigel reminds us, was like ‘a (non) diplomatic bag being returned to sender’.

-

Winged shoes

As he would film in single takes, he didn’t have much film and generally during the last few hours of daylight, Jean Rouch used to say that the intense atmospheres of his shoots reminded him of a jam session ‘between Duke Ellington’s piano and Louis Armstrong’s trumpet’. The camera would entangle and disentangle in a state of Dionysian fecundity, always filming by following the narrative order and trusting that such excitement would lead to a piece of good fortune, like a throw of the dice. Each take was a unique opportunity to succeed or fail (if it didn’t work, the scene was normally thrown out), unleashing the deluge in which both the filmmaker and the actors were immersed. As if the camera were a pencil whose point could be sharpened, the film seemed to be written with the eyes, the ears and the body.

Petit à petit was shot with a minimal team: an assistant, an electrician (best boy) and a sound engineer. A rented apartment in the Trocadéro was used as the base of operations: that’s where they ate, invented scenes and, on occasion, even filmed. When they ran out of ideas, the actors would go out into the street and the camera followed them. The scenes were never rehearsed; locations were visited and positions planned out or, together with the actors, the paths reviewed that would be taken by a camera which, for Rouch, was a combination of Vertov’s mechanical eye and electronic ear and the “shared camera” of Flaherty. Both the Eclair and Aaton camera allowed Rouch to talk to the actors and them to answer, to introduce actions encountered as they went along, reaching an agreement or networking. Sometimes people were suddenly discovered, partially or completely; or they would do or say what is only said or done because of the camera, a pretext or disruptive factor that accelerates phenomena and provokes and transforms the object. In this state of grace, the camera, liberated, would walk and jump from one point to another as if in a dream, it would travel on flying carpets and float with the winged shoes of Rimbaud.

Being invisible by being close. The “contact camera”, with its short focal length, made it possible to see everything and, at the same time, reduce proximity. The use of wide angles allowed Rouch to paint with movement, to film colour, to record moments that were pure questions. Rouch claimed that, when he looked through the viewfinder, he was the first person to see his film, constructing it inside the camera. For him, filming was the first phase in the montage. At the time of Jaguar, when the film was shot without sound, Rouch would cut during the takes themselves; he would stop whenever he got bored, change the angle and press the button again. In other words, he edited while filming; in fact, in Jaguar there were whole scenes without a single splice. But with live sound, any cut would result in a change in all the material, both before and after. But just as cuts shouldn’t be made in the middle of a sentence or song (‘the prejudices of radio’ Rouch used to say), neither should cohesion be achieved by cutting out a conversation within a take. Gradually shaping the material, working on “approximate edits”, the true script (it’s said that work always began with the conclusions and then modifications were made at the end) came to light in the Moviola, when Rouch would systematically take notes. The editor, the second “ciné-eye”, was never allowed to attend the shoot because the filmmaker was waiting for his surprised reaction when he replayed a take; another moment of grace.

Rouch says that it was Jacques Tati who taught him how to gauge the frames in the edit. Contrary to popular opinion, the last image of a shot is always the important one, not the first. So different montages were tested and codas determined for each shot, sometimes regrouped according to a principle of equivalence. For the dreamlike moments, authentic “passports to the imaginary” that have been compared with surrealist paintings, more real reproduction procedures were used to create what was unreal. This is the case of the editing that contrasts work with fun in the long version of Petit à petit: Ariane crushes her hands against the glass of the offices; Safi strolls in a transparent veil and sunbathes on the beach, naked. The impact of these images against the first shot of seams in a rock, somehow condensing the bad omens associated with the new skyscraper, results in a kind of spell: Ariane and Safi, lying on the blue tiles of an empty swimming pool, holding hands, mechanically repeat the words “petit à petit”. Suddenly, the sign bearing the name of the company is falling; the conspiracy of the sleepwalking bodies, the result of fatigue, materialises on the red tiles of the new building. Fantasies collapse; the chapter of lost illusions begins.

-

Lost Illusions

In conversation with Jean-Luc Godard at the time of Petit à petit, Jean Rouch came up with the beautiful utopia of making a 23-hour film, with the idea that it would be projected every day, uninterruptedly, with one hour’s difference. That way, in 24 days you could see the whole film if you went to the cinema at the same time every day. Thanks to his experiences with film lengths, Rouch discovered that time was transformed into space: for example, Jaguar, the seed of Petit à petit, was screened in a 3-hour version at the Cinémathèque. And the 10 hours of rushes from Petit à Petit, screened at a cinema on the Champs Elysées in the order of the scenes, were the inspiration for Jacques Rivette when he shot and edited Out 1.

At that time the editing room seemed to spawn different versions. In the case of Petit à petit, the short was made up of three half-hour parts while the long version (the original) was divided into three episodes of an hour and a half, providing a better understanding of the nature of the project. The title of the first part, Lettres persanes, is associated with Montesquieu’s epistolary novel, in which two Persian travellers write to their friends telling them of their impressions of French society[1]. The digressions and fragmentary state of the letters in the long version are consistent with Montesquieu’s anthropological work, diluted, like Petit à petit, into different voices. The title of the second episode, Afrique sur Seine, is a tribute to the first film made by Africans in Paris. Paulin Vieyra’s project was an ethnological documentary, as was Rouch’s film, designed “in reverse”. The third part, L’Imagination au pouvoir, refers to the time of the shoot itself, postponed from May to September 1968. ‘Once a movement has been started’, Rouch used to say, ‘it doesn’t stop’. His film not only reflected on the possibilities of anarchism as a means to an end but also depicted post-May Paris.

The long version of Petit à petit also provides greater insight into certain incitements in cultural and economic terms. Although, in the film’s original length, the building continues to exemplify, as Fran Benavente points out, an ancestral image of power, an obsession of the economic well-being of capitalism[2] without a real value of use (from the fish and millet store to the stable and harem), a “prologue” shows the changes in the organisation of the old and now rich company in terms of fishing and stockbreeding, transformations where industrial development is confused with Western civilisation, resulting in the purest competitive ambition.

Rouch used to say that, when a Griot dies, a whole library is lost. The non-linear structure of Petit à petit is reminiscent of Africa’s legends and tales. The original montage shows unknown scenes, such as the recording of Lam’s first impressions of a city he had idealised, from the Arc de Triomphe and tourist slides to the shop windows, neon lights and illuminated fountains of the Parisian night, the great dinner in Safi’s psychotropic apartment, the dance where they meet Ariane for the first time and the private meeting between the two young women in which they consider leaving for Africa. The fabric of Petit à petit seems to infinitely multiply, as in the separate plot in which a new character is introduced, that of the blonde girl with whom Lam starts an affair, as well as the storyline of his mother who’ll inform him, shortly afterwards, that his daughter is pregnant. After the entering and exiting the girl’s apartment through the window, jumping in time, Lam spies on them and realises he’s been deceived, hearing how they announce the same news to another man, a story that he himself tells to Damouré in a humorous tone, among inserts and parentheses

In the higher zones of Paris, such as the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont and the Sacré Cœur, Rouch depicts the city’s physical and human geographies. In front of a large map, Damouré imagines new “mountainous” trajectories while Lam, who doesn’t comprehend just how big the city is, genuinely confuses the outskirts of Paris with Toulouse. Thanks to the long running time, Rouch manages to sustain the recurring wordplay with the names of the Parisian streets but also to establish a series of authentic geographies based on false topographies, such as the unique ascending movement (while maintaining the same soundtrack) in Montmartre, where Lam and Damouré are propelled to the snowy peak of Mont Blanc, afterwards reappearing at the steps of a metro station. Even the order of the scenes differs from one version to the other. In the short version, for instance, the steps lead to another place while, in the long version, Lam and Damouré travel through Italy from south to north.

In Petit à petit, distant places seem close in cinematographic terms, such as when Lam and Damouré teletransport themselves from Paris’s working class districts to landscaped villas where some Japanese women offer them food, or from what look like Roman ruins to the trulli of Brindisi, stone cabins that remind them of their straw huts in Niger. Perhaps it’s the feeling of nostalgia that overcomes them which strengthens the insert of a silent montage in which we see the African huts, an associative fantasy that was shot using a different kind of film, nevertheless maintaining the sounds of the Italian traffic, as if they’d been swallowed up by a time tunnel, like the one that literally makes them appear in Camogli, or like the other one that takes them from Genoa (in an allusion to Christopher Columbus who, according to Damouré, ‘took the skyscrapers to America’) to Sunset Boulevard[3]. When, now in Africa, the Castel del Monte appears in the middle of Safi’s singing, a place she has never visited (unlike Lam and Damouré, who one night lead us towards these images), one has the impression that such dreamlike flights are contagious, as if the full moon of the savannah had made them toss and turn in their sleep.

Instead of opening a window onto an unknown world, in Petit à petit Rouch opens a window onto his own world, as if it were a mirror reflecting the image of the absurd model exported by the West and calligraphed by the characters in Africa (the Parisian architect designs the structure of the building without even visiting the place where it will be built). The import-export company demonstrates a second perverse exchange: not only is its goal to sell at a higher price than it buys, as if one man could represent the whole onset of capitalism in Africa, but the characters are also as exotically transplanted as the building itself. Hence, as a consequence, the privileges of Ariane (a better paid but less qualified Parisian typist than the exploited African typist) and of Safi (an African woman who perhaps sees herself as European, or at least “different”, and who very probably has returned with an idealistic view of Africa: the lions, the giraffes!). Faced with these inserts and the impossibility of adopting the model of the other (the tramp misses his wine), the young women do not plan to return to Europe but imagine Dakar to be an African version of Paris, where they can escape the daily banality of Ayourou.

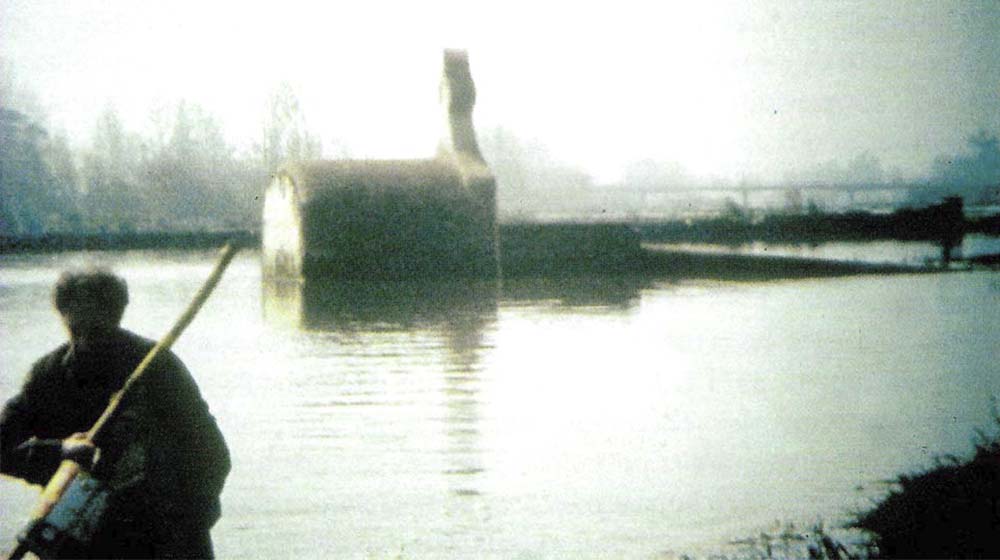

The chimera of the building is finally revealed to be a “poisoned chalice”. When the rowing boats (the initial image of the long version) take the place of the motorised canoes once again, when the horse is chosen over the Land Rover, one has the feeling that an entire circle has been completed. There is planning, testing, failure and a new beginning. On the one hand, Jean Rouch knows that a lifetime is not enough to complete his work but rather several generations of researchers are needed. In Africa, children play at being adults; they cook and spy; they’re present throughout the film, be it in Safi’s story in Paris or in southern Italy, and even a baby leads to a shot of inverted reality, with the sky reflected in the water.

‘You’re young, you’re in a hurry, go on’: the new utopia consists of establishing a secret society where people have time. ‘I’m stopping here; you go on’: as in the habitual Rouchian pedagogy so prone to “false endings”, every arrival in the journey implies a new departure. This questioning, this weighing up that only offers half-answers, as the filmmaker said, allowed him to distinguish between his reactionary and his revolutionary friends. How can a culture survive or simply continue being transmitted when another is devouring it? On the one hand, there was the subsistence economy which seemed to guarantee independence through fishing, agriculture and stockbreeding; on the other, the industrial and technological dependence of the internal systems of televisions and the walkie-talkie communication imagined by the cineaste for the new company. But the “society of old idiots” did not want to return to the pre-colonisation model, nor was it a question, as Rouch reminds us, of swapping skyscrapers for huts, of idealising nature and life in the wild. Damouré and Lam aren’t going to retire but are merely stopping for a moment to reflect and establish a culture which will not be the same as any that has gone before. Having money to spend: this agenda entails, above all, never importing any kind of model again.

At the end of the film, in a play on words, they say: ‘“Little by little” has become “A lot by a lot”‘. Grand à grand was the new project Rouch had imagined, a film in which Damouré, Lam and Illo would become gurus, and hippies from all over the world would seek out their advice; they would have a prisoner called Rouch who would have a camera thanks to which the imaginary would become real. Throughout Petit à petit, Damouré experiences his own metamorphosis; he has also completed his cycle. We can easily imagine these words in the last few pages of his diary: ‘Africa is like a pedestrian running after a bicycle, the bicycle running after a motorbike, the motorbike after a car, the car after a train and the train after an airplane; none of them ever catching up with the one in front’.

Construction and deconstruction:

Benavente, Fran. Jean Rouch. Puentes y caminos. Barcelona: Intermedio, 2008.

Bregstein, Philo. “Jean Rouch, fiction film pioneer: a personal account”. Building Bridges: The Cinema of Jean Rouch. Columbia: Wallflower Press, 2008.

Deleuze, Gilles. L’Image-temps. Paris: Editions de Minuit, 1985.

Fieschi, Jean-André and Rouch, Jean. “De Jaguar à Petit à petit”. Cahiers du cinéma, no. 200-201, April-May, 1968.

Fulchignoni, Enrico. “Conversation avec Jean Rouch”. CinémAction, no. 17, “Jean Rouch, un griot gaulois”. Dossier de René Prédal. 1982.

Rouch, Jean. “Je suis mon premier spectateur”. Paris: Le Monde, 1 September 1971.

Rouch, Jean, “La caméra et les hommes”, in de France, Claudine (Ed.). Pour une anthropologie visuelle. Cahiers de l’Homme. Paris: Haia, Mouton Éditeur, E.H.E.S.S.

Rouch, Jean. “La mise en scène de la réalité et le point de vue documentaire sur l’imaginaire”, in Jean Rouch: Une rétrospective. Gallet, Pascal-Emmanuel (Ed.). Paris: Ministère de relations extérieures/Centre National de Recherches Scientifiques, 1981.

Scheinfeigel, Maxime. Jean Rouch. Paris: CNRS, 2008.

Toffetti, Sergio. “Ma vie en Rouch”. Jean Rouch. Paris: Édition du Jeu de Paume, 1996.

[1] ‘Paris is as large as Isfahan. Its houses are so tall that you’d swear they’re occupied only by astrologers. As you’ll imagine, a city built in the air, where six or seven houses are piled one upon the other, has a huge population and when all the people come down from their houses, the crowding and confusion in the street is amazing. You’ll find this hard to believe but, in the month I’ve been here, I have yet to see anyone walking; there can be no nation in the world that makes their bodies work harder than the French. They run, they fly; the slow conveyances of Asia, the deliberate, even steps of our camels, would give them a heart attack’ (Letter 24, From Rica to Ibben (at Smyrna), Montesquieu, Persian Letters.

[2] It’s not that the finished building looks like a hotel but rather it was filmed in a hotel. In his statement of intent, Rouch talks about filming in the Hotel Ivoire in Abidjan.

[3] Damouré and Lam never travelled to America but Rouch believed it was essential for them to discover it in fiction. In the statement of intent he explains that he would shoot this material by himself, during trips to the United States or Montreal, and that these shots would probably be intertwined with others filmed in Paris, at La Défense.