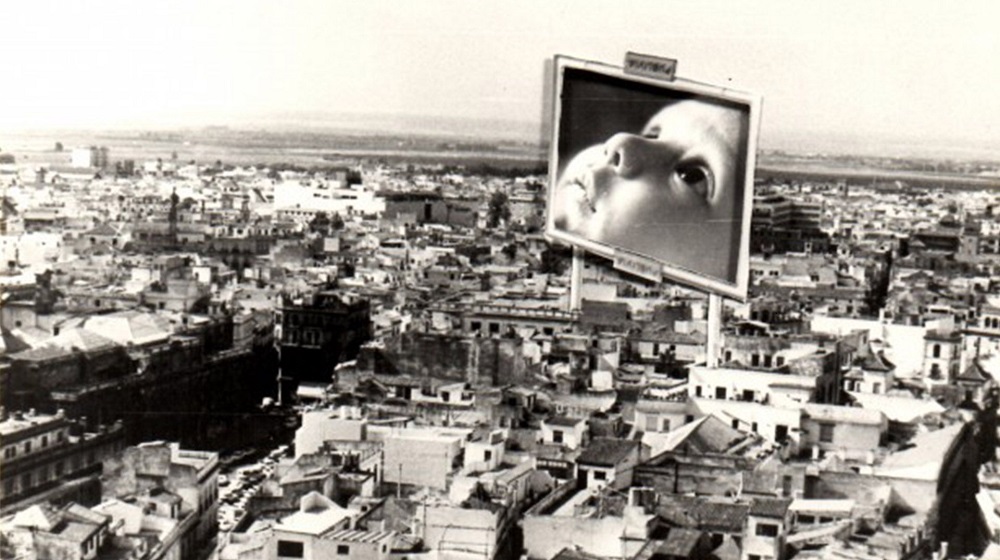

Sevilla tuvo que ser (Seville Had to Be; J.S. Bollaín, 1978) is at the same time a science fiction documentary and a film found in the rubbish, in the style of Weekend (Godard, 1967), which said of itself: “a film lost in the cosmos; a film found in the rubbish”. Sevilla tuvo que ser passes itself off as an old news programme found by chance – no unusual occurrence. So many films have been lost and found in the trash, and so many news programmes have been strategically forgotten in a pile of reels in the middle of some storage room, or left on the street to be picked up by the bin lorry. I’m thinking of the hundreds and hundreds of reels filmed by Antoni Muntadas in TVE: primer intento (TVE: First Attempt; 1989) as part of the mechanism of rhetorical looting – the replacement of the word censorship with “commercially unviable” – and of how Bollaín takes the source of this everyday catastrophe, uses it as a narrative device and, perhaps also, as an attempt to navigate his own danger of censorship with humour and fictional detachment. This refuse collector’s news piece talks about the superiority of Seville over all the other cities in the world, being as it is the only one that has managed to avoid the endless spiral of decay that is starting to push people as far away as possible from urban areas. What is Seville’s main solution for countering its own obsolescence? To deal with an “erotic crisis” through hypervisibility, filling the city with screens that show porn all day long, “for the pleasure of young and old”. Inspired by these screens, the architects, city planners and designers lay plans for a city full of giant breasts and penises. This hypervisibility, rather than leading to desensitisation and a technocratic dystopia, paves the way for an urban transformation that finally opens the city up to nature. Suddenly the sunlight, the tides, the movements of the moon and the sound of the sea become the sensorial heart of the city. One of the last points in this experiential revolution shown in the news programme is the appearance in the streets of a series of intimate events which are broadcast and amplified (letter to my boyfriend aired, for example), while even the concept of monuments is transformed – they no longer commemorate military scenes, religious figures and the like, rather moments start to spring up that are related more to everyday life, such as the Monument to the Day I Had a Really Good Time in This Square. Through a series of stimuli from the screens, Seville suddenly becomes hypersensitive to everything – a city dedicated to the pleasures of experience, amplified. In this sense, Sevilla tuvo que ser is a utopia, a dystopia and at the same time an illustrated and even slightly futuristic short history of film (that includes all the good and all the bad things that surround us) in which the influence of Astruc’s concept of the caméra-stylo literally materialises (as has previously happened and still happens today) not only in the world of film, but in all spheres of life, even in city planning.

Nowadays, a world full of intimate domestic images is the everyday norm. As Claudio Caldini said in the same year that Bollaín made his film, “The 35-mm veterans sigh: ‘Nowadays anyone can film…’. That’s precisely the point”. In any case, this ideal which sounded crazy in Bollaín’s film, but which Caldini was already heralding as a happy reality, only came partly to pass. Nowadays anyone can film, but who screens the work? The film industry has been suffering from a distribution crisis since the day it was born, a crisis that expands as its output grows and the technology moves forward. Perhaps its hierarchies have always been behind the times? The caméra-stylo gets good press, but the projector-stylo has been criminalised, and the history of film-stylo doesn’t have a very high standing. Images are constantly being produced in new, free ways, but not so the circulation of these images. As for the stories told by moving images, even today those that come with the institutional seal of approval as Official History are still given precedence. Rather than being celebrated, the pirates of moving image, with the exception of Henri Langlois, are disregarded and their work does not go down in the annals of history. This work comes in many shapes and sizes – opening up hidden spaces in the history of film in places where sometimes even the most enlightened fail to reach, creating subtitles, discussions, translations… basically, an endless output of invaluable knowledge which is discredited as being immaterial. In the history of the circulation of moving images, there is no mention of non-institutional access such as formal piracy (torrents, direct downloads) or informal piracy (file exchanges between friends and peer-to-peer networks, one by one). The knowledge that many of us have in the community of writers, curators and thinkers in the world of film, seems to have been gained as if by magic, through exposure to large chunks of a hidden history of film that was generated spontaneously, although mostly it is pirated.

This is unfair not only because any kind of concealment of this type is unfair, but also because it wipes away a type of history that is in danger of being quickly forgotten. If the official history of film is patriarchal, racist, classist and in many other ways violent and insufficient, how can we navigate along these shores that we are creating, so different and beautiful, those of the alternative histories? How can we know about the outliers if there is no time and no money to visit archives, to take classes in all the different countries, to meet all the people we could ask questions to? The internet, of course. One option for some, the only option for others. In Trelew, a small city in Argentina where I first delved into piracy, there has never been a retrospective of Rose Lowder, neither do I think there will be one in the next 10 or 20 years. And if I hadn’t known who Rose Lowder was, I might never have received a grant for the very expensive university I went to and where, from time to time, they rented a copy of her Bouquets. Almost all of us who make our living from this, except for the millionaires – and I don’t know any – lead a double life: one the one hand, we work day and night so that the history of film that we believe to be important can get as much exposure as possible, and in the best possible material conditions, and on the other hand, we watch and download digitalised VHS copies, with lousy quality or recorded off the TV, washed out colours and terrible sound, to gain some understanding of what’s out there, so we can put together a history, our own version of history, and then share it, materialise it. Just like with Bollaín’s screens, with the history of film everything is back to front – first the loophole, then the law.

Any objection to this, to that fact that nowadays anyone can see or screen a film is, in this sense, pretty stingy. Allowing everyone to access material shouldn’t be a utopic ideal. Perhaps the conditions for a film forming part of the history of film shouldn’t be whether or not it is available, but rather the richness of its ideas, and those that are generated after seeing, organising and relating them. Here there is also a hidden richness – that of the small epic of the film’s circulation, and the finite and specific number of people who were involved in creating this poor image, as Hito Steyerl would say. In a very recent book by Erika Balsom on Ten Skies, the famous film by James Benning, towards the end, toying with the question that we all ask ourselves, i.e. how could this women watch this film in so much detail, so many times?, she says that she has been watching Benning’s film on YouTube, before going on to describe how the film can be watched legally and in the perfect material conditions – a 16 mm copy – and the cost that this would involve which, for her at this time, would be exorbitant. Balsom tells how, slightly fearfully, she confessed to Benning what she was doing, and Benning replied, “sharing is caring”. Ten Skies films ten skies for ten minutes each. The film has a lot of ideas behind it, an awful lot, and this represents work, work that should be valued. The sky, meanwhile, belongs to everyone, as does film. These two truths are not mutually exclusive. Perhaps, going back to Bollaín, hyper-exposure and hyper- availability are not bad in themselves (although we could clearly go crazy). Neither is a double life; the problem is how to enrich the experience, how to regain sensory clarity in this sea of films, in this rubbish bin, in which every tiny gesture, every exchange, has the ability to make film a little more our own. As I continue to ponder over these things, the image comes to mind of a small screw in a metal plate, forgotten among the dirt on the floor of a factory that’s about to close. It’s the closing scene of Kodak, by Tacita Dean, a film shot in the Kodak factory in France after the company decided to stop producing film. This screw – why is it there? Before, every object played a part in producing the material for shooting films, and now this screw has no use, it will be just one more object in a pile of refuse, like a load of reels left in the trash. Internet will also have its crews, all the time, on the verge of disappearing.

Lucía Salas

*The films of J.S. Bollaín have recently been available online and screened thanks to a retrospective of his work organised by the S8 festival. Sevilla tuvo que ser is also available on Plat and YouTube.

*Thank you to Sonia García Lopez and Miguel Zozaya, my dear historians in this adoptive country.