The Japanese experimental filmmakers featured in this programme can be roughly divided into three generations. First, Takahiko Iimura (1937-2022), whose film entitled The Pacific Ocean (1971) is the first to be screened, is one of the first generation of post-war Japanese experimental filmmakers. Whilst involved in the contemporary avant-garde art movement Neo-Dada, in 1961 he also established Firumu Andepandan (Film Independent) together with Nobuhiko Obayashi, Donald Richie, Yoichi Takabayashi and others to produce and organize screenings of experimental films, partly laying the foundations for the subsequent rise of Japanese experimental film.

In the mid-1960s, organizations such as the Sogetsu Art Center (founded by the creator of the Sogetsu Ikebana School) started to include American underground cinema in its programming. Works by filmmakers such as Stan Brakhage, Bruce Bailey, Paul Sharits and Stan Vanderbeek were seen for the very first time, although it also helped to promote Japan’s underground youth culture which was experiencing a boom at that time, through theatre, happenings and other art forms.

The next generation emerged under such influences, such as Junichi Okuyama (1947-) and Hiroshi Yamazaki (1946-2017). Junichi Okuyama's first film was Mu (1964), shot while he was still at high school, but he became known and made his name as an experimental filmmaker when Bang Voyage (1967) was selected for the Tokyo Film Art Festival in 1968, an experimental film festival organized by the Sogetsu Art Center. Known as a photographer, Hiroshi Yamazaki began making 16mm films in 1972 after being invited to work with the medium by Sakumi Hagiwara, a filmmaker from the same generation who was involved with Shuji Terayama's theatre troupe, Tenjo-sajiki.

The end of the 1960s was a time when this underground culture truly blossomed, a time when various social movements were also at their peak, especially among students, such as the movement against the revision of the Security Treaty between the US and Japan, the anti-war movement in Vietnam and the Narita Struggle. The rise of underground cinema was also supported and developed mainly by the younger generation, who questioned the existing social framework and forms of artistic expression. However, in the early 1970s these social and cultural movements suddenly receded (the aforementioned Film Art Festival was cancelled in 1969 and the Sogetsu Art Center disbanded in 1971). The fervour of underground culture, which had been a kind of fad, also began to wane and the introduction of avant-garde works from abroad became more subdued compared to the 1960s. However, artists in the experimental field continued to collaborate and interact with each other through screenings and related activities and, thanks to this close connection, a unique Japanese experimental film culture was nurtured throughout the 1970s and 1980s. The generation that emerged at this time is the third in this programme and includes Akihiko Morishita (1952-), Takashi Ito (1956-) and Itaru Kato (1958-).

Akihiko Morishita and Takashi Ito were students of Toshio Matsumoto (1932-2017), who came from the first generation of experimental filmmakers in post-war Japan, during his time teaching at the Kyushu Institute of Design. Itaru Kato was a student of the Image Forum Institute, set up in 1977 by Image Forum to encourage a new generation of experimental filmmakers.

During the 1970s and 1980s, two main trends can be seen in Japanese experimental film: an approach which could be called “structural cinema” and also personal diary or essay filmmaking. Most of the works featured in this year's programme are more akin to the structuralist approach. Several films of this type have been rediscovered outside Japan in recent years but films from the other trend, namely personal diaries or essays, have yet to become known overseas. The works of filmmakers such as Shirouyasu Suzuki and Nobuhiro Kawanaka from the 1970s and onward, as well as those by young female filmmakers who focused on the themes of the body, family and sexuality in the 1990s, are nonetheless significant in the history of Japanese experimental film.

Many of the films presented in this programme are conceptually related to the structural filmmaking approach. However, each work differs in terms of how the subject is treated and what is captured as an image.

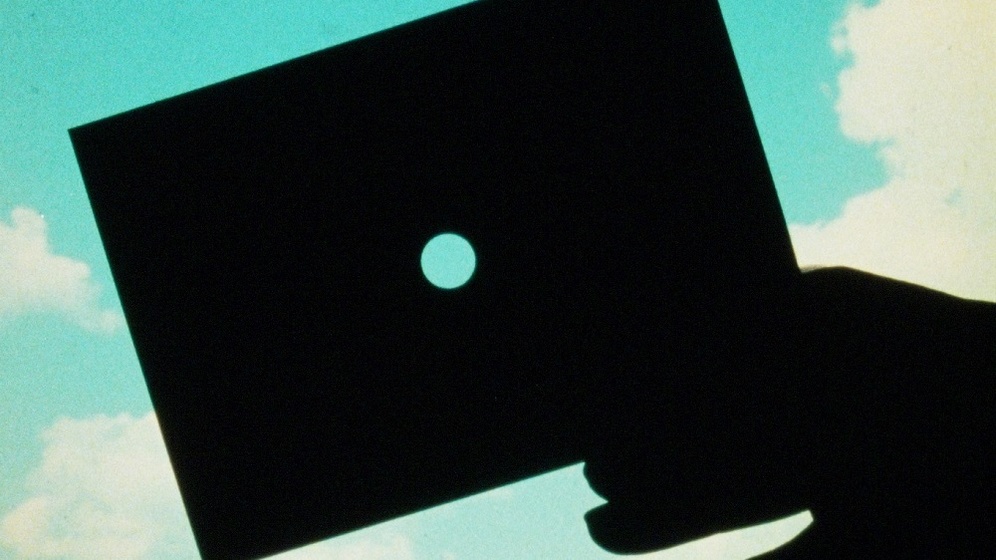

Iimura's films from the early 70s tend to be more abstract and create distance from the image. He almost seems to lose interest in what’s in front of the camera, becoming more interested in the question “what could be the most minor image in the cinema experience?” Moving to New York and being exposed to the conceptual art there, Iimura began to produce works which deal heavily with logic, eliminating the sensory aspect of images, eventually expanding his activities to video art and installations, as well as approaches to contemporary art.

For Junichi Okuyama, who’s been making “films about analogue films” since the 1960s, most of his subjects are chosen for the concept of the work in question. For example, ocean waves were chosen for Movie Watching (1982) because he needed to have a horizontal subject to show the concept of the image shifting between each perforation of the 35mm film (which you’ll see as a “mistake” by the projectionist during the screening).

As a photographer, Hiroshi Yamazaki questioned the act of “choosing a good subject” and selected the universal subject to be shot, such as the sea, along with the sun and cherry blossom. His photographic works overlap with his films in terms of location and technical approach controlling exposures (for instance, there’s a series of photos called “Heliography” which was produced around the same time as the film shown in the programme). The horizon in Yamazaki's Heliography (1979) isn’t presented horizontally but tilted on the screen.

As for Takashi Ito's Spacy (1980), it would be a stretch to say that the only location available for him that could fulfil the conditions required to realize the concept of the piece was this gymnasium (which belonged to the university he attended), but Ito's recent works have been more in the direction of narrative films, in collaboration with performers, dancers and actors. In fact, it’s interesting to note the shift in his approach regarding the subject throughout his filmography after the 90s.

Many of Itaru Kato's early works are stoic structural films that explore camera mechanisms such as shutter speed, focus and depth of field. Wiper (1985), made at a time when Kato said he was “in a slump”, is a multiple-exposure composite film that focuses on a car’s windscreen wiper as a subject to demonstrate a “wipe”, a special effect used in film. The piece has a light sense of humour for a film made during a slump, together with another multi-exposure film Washer (1987), which was made at the same time.

Akihiko Morishita astonished viewers with his magical visual technique in Xénogénès (1981), in which a skinny man in trousers walks around in a figure of eight, lightly crossing over and behind the scratch lines on the surface of the image (also partly used as an image in the film Xérophtalmie included in the programme). As he calls himself a “media artist” rather than a filmmaker, Morishita’s interest extends beyond cinema to various visual media. His works can be described as postmodern meta-image pieces that focus on the relationship between the images and what they represent.

Koyo Yamashita