Until the 2011 retrospective organized by the UCLA Film and Television Archive entitled L.A. Rebellion: Creating a New Black Cinema, the works of the Los Angeles School of Black Filmmakers, a pioneering movement of young African-American filmmakers at UCLA in the 1970s, were known only to a few specialists. Passing Through, the second film by Larry Clark, had become a milestone of African American cinema, and its director one of the key members of the group that the academic Clyde Taylor would re-christen the L.A. Rebellion. The importance given to form and the experience of viewing of the original led its director to refuse VHS distribution in the 1990s after a successful run at independent cinemas. What the French critic Raphaël Basan (Libération, 1985) would call “the only jazz film in history” would be forgotten, despite receiving the Special Jury Prize at Locarno, after a debut at Filmex in L.A, in 1977 and a tour through the festival circuit.

The film appeared at the end of a decade that saw the beginnings of the rules surrounding the production, distribution, and audiovisual aesthetics of African American artworks as we know them today. The Watts riots (1965), a response to urban segregation, police brutality, and intense opposition to the war in Vietnam, would provoke the creation of L.A. Rebellion. The movement included such kley figures of the radical black tradition as Julie Dash, Charles Burnett, Zeinabu Irene Davis, Haile Gerima, Billy Woodberry, and Jamaa Fanaka. Its political engagement, collaborative working methods, formal experimentation, and opposition to Hollywood cinema would serve as a model in the U.K. in the 1980s for groups like the Black Audio Film Collective, the Film and Video Collective, and Ceddo Film and Video Workshop, which included artists like John Akomfrah, Isaac Julien, and Trevor Mathison. L.A. Rebellion emerged on the U.C.L.A. campus to respond to the needs of communities of color in Los Angeles. It began under the tutelage of Elyseo J. Taylor, the only black professor in the School of Theater, Film, and Television; he would be joined in 1974 by Teshome Gabriel, a distinguished theorist of Third Cinema with roots in Ethiopia. The young directors they oversaw developed their ideas in seminars devoted to Frantz Fanon, Aimé Césaire, and W.E.B. Du Bois; projections of essential works of Latin American Third Cinema, Italian Neorealism, European Film Art, and groundbreaking works by African directors Ousmane Sembène and Djibril Diop Mambéty. While the Black Panthers were everywhere on newspaper covers and television, Larry Clark was presenting his thesis, As Above, So Below (1973) in a novel program whose black aesthetics avoided both commercial Hollywood cinema and the auteur cinema of Europe.

In the 1970s, the Blaxploitation phenomenon exploded. The starting gun was two titles from 1971: Shaft by Gordon Parks and Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song by Melvin Van Peebles, both of them unprecedented landmarks in the creation of African American images and narratives and in their attempt to cultivate a distinctly African American viewing public. The first black TV channels would appear at this time; an experimental and oppositional cinema was born; black urban life was fictionalized as popular entertainment; and a whole series of genre films appeared that would rescue historical figures and events in order to inspire reflections about the present. These tendencies continue in the twenty-first century with artists who move between genres, platforms, and messages, like Ryan Coogler, Ava DuVernay, and Berry Jenkins.

Born into a family of musicians – his uncle was the jazz pianist Sonny Clark – Larry Clark was one of the cameramen for Wattstax (Mel Stuart, 1973), a documentary about the mega-concert known as Black Woodstock, which was sponsored by Stax Records with jazz, R&B, funk, blues, soul, and gospel artists gathering in 1972 to commemorate the seventh anniversary of the Watts Riots. Presented by Jesse Jackson, with standup by a young Richard Pryor and musical performances by Rufus Thomas, The Staples Singers, Eddie Floyd, and – to cap things off – Isaac Hayes, this was a formative experience for the young Clark, who was filming As Above, So Below at the same time. The latter film, politically radical, is 52 minutes of 16mm film examining black resistance in the state of siege imposed on L.A. after the riots. The story of the young Jita-Hadi, a marine veteran, de la marina whose awareness develops as he returns home, has a special connection across time and space with Soleil Ô (1970) by the Mauritanian Med Hondo.

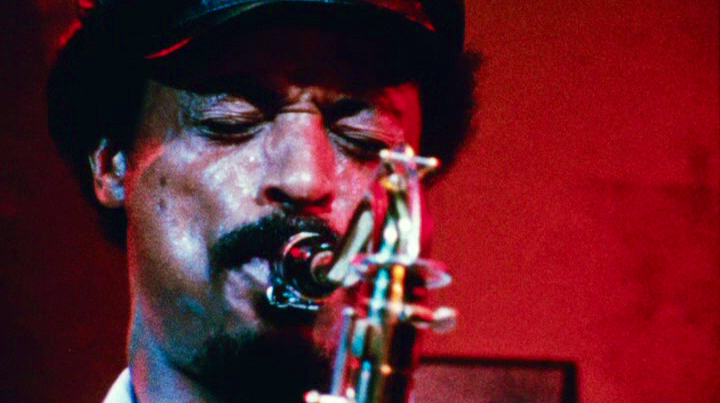

Filmed independently, with community support and a shoestring budget, Passing Through tells the story of Eddie Warmack, a jazz musician fresh out of jail after killing a white gangster. Again, Clark chooses for the starring role Nathaniel Taylor, known as Rollo Lawson from the famous sitcom Sanford and Son (NBC, 1972-1977). Conceiving of jazz as the highest expression of African American culture, encapsulating struggle and resistance from the slavery period to the present, Warmack sets off to find his mentor, the legendary jazz musician Poppa Harris, who taught him the mystical components of jazz in his childhood and will now help him to continue fighting against the exploitation of black artists by the white music industry.

Professor Tina Camp proposes the counter-intuitive practice of listening to images, stressing the centrality of the sonic and its tensions with the visual as a characteristic of radical black art, and the recuperation of archive, drawing on such exemplary films as West Indies (1979) by Med Hondo and Sankofa (1993) by Haile Gerima. With its thematizing of unknown stories and its experimental soundtrack, Passing Through takes part in the same tradition, attempting to replicate in cinema a black aesthetics already present in jazz. Avoiding linear narration, assembling plots according to the narrative models of African oral traditions, Larry Clark draws on collage, cubism, and jazz with their improvisations and superimpositions, highlighting transitions and unexpected connections. In this meditation on memory, fragments of time rise up and linger like scars of black history. The constant movement implied by the title alludes to the interpenetration of histories and temporalities and to the movement of the protagonist himself through the city, recalling the itinerary of Anta y Mory in Touki Bouki (1973), a classic of African avant-garde cinema by the Senegalese Djibril Diop Mambéty.

Seven minutes of a jazz concert serve as a prologue, in a brilliant homage to music and its creators, followed by a palimpsest of interposed whites, blues, and reds fading to blue. The director remarks that two visual elements were paramount in searching for a setting: jazz L.P.s and the small, intimate clubs where he listened to jazz under blue lights. Perhaps Miles Davis’s Sketches of Spain (1960) was the basis for the following scene, with the protagonist playing saxophone in profile under the L.A. docks surrounded by water. A wave (bought as unused stock footage from The Ten Commandments) and the music incite a transition into the last. In Passing Through, Clark maintains the classic structure of three acts while discarding traditional narrative to convey the improvisational character of jazz through flashes forward and back, free movements of the camera, and a blend of archival footage and reconstructed scenes (the Attica prison riots of 1971; still photos of black revolutionary leaders). The film’s soundtrack, composed by Horace Tapscott and performed by the Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra (P.A.P.A. o The Ark), is an effort at pursuing art through community - Tapscott formed the Arkestra in 1961 as a response to the racial inequalities of the time.

This is the only film about jazz that also possesses the structure of jazz, with the exception of Ornette Coleman, Made in America (1985) by Shirley Clarke, which takes as its point of departure Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic domes, those geometrical forms that inspired the harmolodic theory of the saxophonist Coleman, an essential figure of free jazz.

Four decades after its debut, Passing Through retains powerful echoes among the Afro-diasporic population. Viewed against the backdrop of Black Lives Matter, the struggles for representation in the mainstream audiovisual industry, and debates about the role of imagery in the recovery of memory and buried archives, the film is an example of multiple resistances that can permit a young generation to reflect on and reevaluate their agency in history.

Beatriz Leal Riesco