Little Big Town is small.

It has one road called Long Street.

They say that if you walk down the street in one direction, you’ll see the sunrise.

And if you walk in the other direction, you’ll see the sunset.

Karpopotnik (Matjaž Ivanišin, 2013)

Alienated and non-aligned

Yugoslavia. Late sixties, early seventies. Josip Broz, otherwise known as “Tito”, had long since sent the other Josip away (1948). And that singular, fearless decision had launched the state of Yugoslavia into a new orbit known as the “non-aligned movement” or “third way” (1961). The country was moving forward unfettered by Soviet imposition but also without being absorbed by the West, implementing a hybrid Marxist-liberal economic system. A brave oddity made up of improvisation and political experimentation.

This strange duality, which worked relatively well and which some citizens long for today, could also be found in how the country’s national complexities were handled; a duality that was also a “stick and carrot” strategy. When one of Yugoslavia’s regions erupted in a tsunami of protests spurred on by the Prague Spring and May ‘68 (Croatian Spring, 1971,) the regime was relentless in its repression, as it inevitably was with all dissidents. But not long afterwards, that same authoritarian state rewrote the Constitution (1974) and approved a large number of the demands made by the students, nationalists and intellectuals who had come out onto the streets to protest. Essentially the state was further decentralised, with the regions gaining more autonomy and self-management. But the nation managed to maintain its backbone that acted as the mainstay for so many checks and balances, on the one hand thanks to the charismatic figure of Tito and, on the other, the great renown enjoyed by the army, benefitting from the epic local victory achieved in World War II. Cinema, literature, newsreels, comics and propaganda, among other organs of the establishment, were responsible for keeping the ideological flame alive - until everything burned.

Une jeunesse yougoslave

In the early 1950s, the country’s versatility was also reflected in its cinema. Through official channels, national mainstream films with a socialist aesthetic and creed were produced but, in an attempt to open up the country to other perspectives, Western films were also allowed to be shown in commercial cinemas. And, as a third way, the first amateur film clubs were set up “under the auspices of the ‘Narodna tehnika’ (People’s Technology), a policy aimed at technically enlightening workers through amateur clubs”.[1] There were no film schools yet and this state-funded milieu of cultural development became the breeding ground for a powerful movement. The generation that, a decade later, would lead the New Yugoslav Cinema, also known as the “Black Wave”, was forged in those modest film clubs dotted throughout the country (Ljubljana, Zagreb, Split, Novi Sad, Belgrade and others).

The film clubs’ members started making their own films, especially shorts. They set up gatherings, competitions and awards, stimulating a creative movement. They turned to the avant-garde, the investigation of language and aesthetics, and also touched on controversial topics. According to curator Ana Janevski “we can divide their films into two categories, although they are interlinked. The first are films that aim to show the dark side of the country, presented as perfect by the government. These are the filmmakers who’ll be most professionally connected to the later films of the Black Wave (black because they wanted to show that “dark” side), and these are the ones that had problems with censorship. The other category is more linked to the arts, with their films focusing on the process of film, on the medium, working with matter without the need to tell stories. They had no problems with censorship and were also connected with art galleries beyond the cinema, galleries where a large part of them ended up developing their professional careers”.[2]

This jeunesse yougoslave, sons of war, the source of partisans and assorted repression, did not remain silent regarding the restrictions imposed by the establishment. The group involved in producing feature films started to tell stories and, within these, began to investigate themes with a subversive bias, and to express unofficial points of view. What was worked on and discussed at the film clubs bore fruit in those who’d been members in their youth, and names such as Živojin Pavlović, Aleksandar Petrović, Lordan Zafranović, Želimir Žilnik and Dušan Makavejev, among others, came to the fore in this “wave”.

Karpo’s trail

In recent years, looking at the period before the Black Wave, at the modest but numerous and powerful movement by the film clubs in that peculiar state, a treasure has been salvaged: the short films of Karpo Godina. As time went by, his name was hidden as a filmmaker for two reasons: first, because he forged his reputation above all as a director of photography, being considered one of the best in the country and highly sought after. And, secondly, because the government began to crush the Black Wave, restricting its freedom and making work impossible in the 70s. In some cases this persecution forced them to move abroad to stay in the film industry, thereby dismantling much of the troublesome movement.

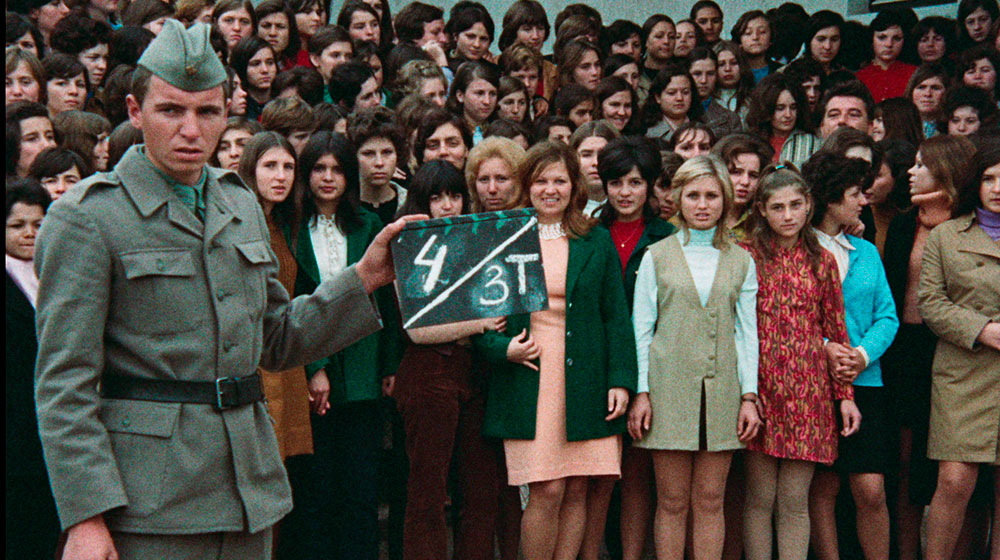

Godina’s short films have been slowly been recovered. For about a decade, thanks to research and the odd DVD, his shorts from the early 1970s, filmed in colour, have been revitalised. It was worth bringing these to light because, even after fifty years, they have retained all their fire, fun, subversion, immoderation, creativity, beauty, jokes, improvisation, madness and genius. Later, in 2015, another part of Godina’s work also appeared. Slovenian programmer and researcher, Jurij Meden, managed to salvage some missing shorts from the 1960s. These black and white pieces, now restored, are largely experimental and focus on the aesthetic, in clear opposition to the official canons of the time, and provide more insight into Godina’s work and also that period of filmmaking. To round off the resurgence of Godina, in 2013 Slovenian filmmaker, Matjaž Ivanišin, created the poetic documentary Karpopotnik (something like On Karpo’s Trail), a journey through present-day Vojvodina using reels that Godina had filmed while travelling there, fragments of an unfinished and forgotten film.

If there’s one thing all these short films by Godina have in common, it’s that they’re full of music and this carries the narrative weight. As in every dictatorship, direct assertions can cause problems so the meaning is not always clear, giving rise to a variety of interpretations. This allows us to speak in metaphors, to insinuate ideas between the lines. I had the chance to interview Godina a few years ago and asked him about the enigmatic nature of some of his work. Although he didn’t answer me, he left two small clues for their interpretation: “I don’t explain meanings; let viewers make their own interpretations. But you have to put yourself in the time and place and also realise that it was the era of LSD”.

PS: About the programme

Today the “Black Wave” movement tends to be forgotten, even by film buffs. From time to time a programme appears that takes a trip into that past. For instance, the MACBA focused on the work of the film clubs (“We can’t promise to do more than an experiment”, 2011) and Xcentric dedicated a remarkable session to the Split film club (“The roots of the Yugoslavian avant-garde movement”, 2019). Internationally, a recent comprehensive retrospective was dedicated to Želimir Žilnik’ (DocLisboa 2015, which later travelled around several international festivals). But not much else. Now that the 25th and 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall has been celebrated and the entire Socialist period in Eastern Europe is being reviewed, perhaps it’s a good time for an in-depth retrospective. It would allow us to weigh up the importance of this cinema, to assess its impact on the Socialist regimes, as well as (always the most delicate of tasks) to see how its films have withstood the passage of time.

Miquel Martí Freixas

[1] Miodrag Miša Milošević, “La época de los cineclubs. Cine y video alternativo en Yugoslavia”, Blogs&Docs, November 2011.

[2] Ibid.