Chilean filmmaker Jaime Barrios arrived in New York City in 1963 to attend the School of Visual Arts and was soon active in an experimental scene, which overlapped with the New York Underground and tightly intertwined with his media activism at the Young Filmaker’s Foundation (YFF). The YFF, founded by art educator Rodger Larson alongside Barrios and New York philanthropist Lynne Hofer, was a community outreach project for New York City youths dedicated to training them in the art of 16mm filmmaking. Later emulated throughout the United States as part of the nationwide War on Poverty, the New York City film workshops served as a blueprint of a brief, yet effervescent, movement.

There is a complex interaction between the gaze, authorship, and the politics of visuality throughout the archival materials that remain of the YFF, including the varied student films of the period, assorted YFF promotional materials, and the two companion manuals published by Larson in 1967 and 1968. However, the complexity of the YFF’s politics of visuality is perhaps best expressed and nowhere more fraught than in Jaime Barrios’ Film Club (1968). A twenty-three-minute documentary film directed by Barrios and produced by Larson, Film Club was released in 1968 with the intention of promoting the programs of the YFF. Now housed in the Reserve Film and Video Collection at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts (NYPL) and the New York Film-Makers’ Cooperative, in its moment of production, the film was supported by the private Helena Rubinstein Foundation and the public New York State Council for the Arts. In addition to serving as an internal recruitment film, Film Club screened at both the Robert Flaherty Film Seminar and the newly inaugurated New York Film Festival (NYFF) yet sidesteps the NYFF’s investment in auteurism or avant-garde as well as the Robert Flaherty Film Seminar’s commitment to direct cinema throughout the 1960s or its growing fascination with explicitly announced documentary reflexivity at the decade’s end. On some level, Film Club shares the processual nature of Chilean documentary of the 1960s and the dominant developmentalist aesthetics common to much postwar Puerto Rican audiovisual and, more broadly, visual production. Yet, as much as it partakes of Great Society principles, Barrios’s documentary lacks a programmatic investment in didacticism or in national processes of collective subject formation that critics have largely associated with the latter traditions. Thus, even as Film Club engages a hybrid documentary lineage, it forges its own relationships with authorship, filmic narrative, and the self-determination of representation.

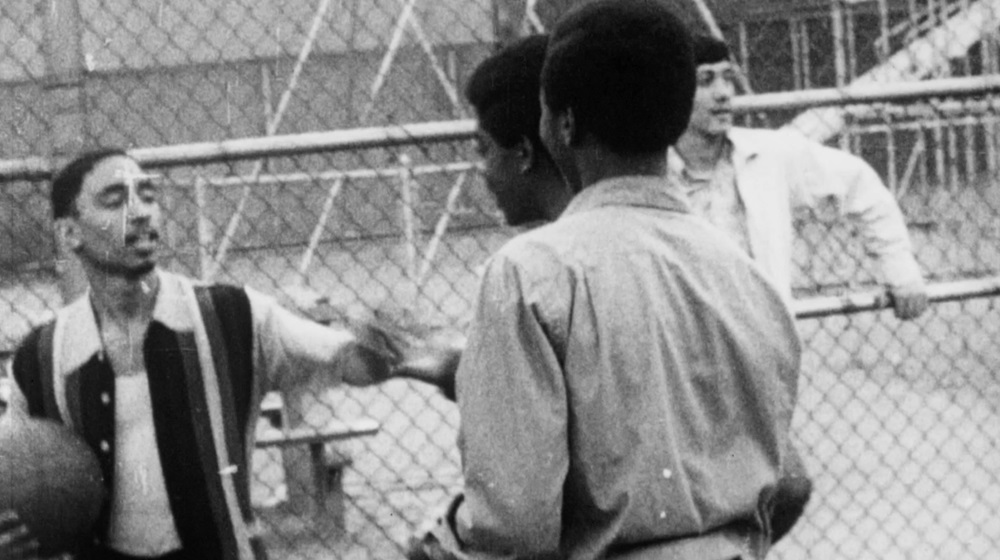

Film Club is structured by a series of behind-the-scenes shots of student productions (most set to music), interviews of administrative figures (including Larson and Hofer), and three student interviews. Despite being called “a film teacher’s diary” in the 1971 catalog Movies from Youth Film Distribution Center, pointing toward the personal first-person singular connotations of the diaristic genre, Film Club’s montage texture and camera perspectives generate the sensation of a collective, composite, and nonhierarchical vision oscillating between Barrios and the student filmmakers, only emphasized by Barrios’s frequent cameos. Even as vision, the eye, and the gaze have long been metaphors and filters through which to understand filmmaking and a broader politics of the image, these visual metaphors populate the discursive and visual material surrounding Film Club with a particular insistence. As such, Film Club constitutes a polyphonic exploration of the politics of viewership and representation. As the documentary weaves through a labyrinth of symbolic investments and variables, ranging from funding organisms, community uplift, and the values of the Lyndon Johnson–era War on Poverty, the student filmmakers portrayed in Film Club reinscribe their own vision of the self through a complex matrix of visual, performative, and rhetorical relations. The subjectivization produced in this operation frustrates any straightforward liberatory identitary narrative. At the same time, the uncertain nature of the film’s authorship, declared proposals, and archivization complicate its place in canonical frameworks, which ultimately opens up the possibility of new critical and spectatorial horizons of expectation for the documentary. Here, visual and moral relations and exigencies are reconfigured, allowing for the reconsideration of the expectations traditionally placed on diasporic subjectivities and canons.

The critical reception (or lack thereof) of Film Club, Jaime Barrios, and the student filmmakers who in many ways share authorship of the film relates to a variety of factors ranging from the gatekeeping logics of festival circuits to the prevailing protocols of film canons. This is perhaps best evidenced by the initial festival screenings in the 1960s of Film Club at the Robert Flaherty Film Seminar and the New York Film Festival, followed by a long intervening silence until the 2000s. In the last half decade, the work of Barrios and of the student filmmakers of the YFF has gained increasing visibility. Barrios’s experimental work of the 1960s and his militant work of the 1980s in response to the Augusto Pinochet dictatorship (1973–1990) in his home country of Chile have recently been examined in a series of pioneering studies, such as those by Julio Ramos, José Miguel Palacios, and Sebastián Figueroa. The Young Filmaker’s Foundation has likewise been explored in important research by Elena Rossi-Snook, Lauren Tilton, and Noelle Griffis. The latter studies each provide invaluable angles from which to appreciate the Barrios constellation, to which my own research on Film Club has also contributed. This nascent yet growing critical interest speaks to a shifting horizon that the reception of an artist and a movement may undergo with the passage of time through the eyes of a new generation of viewers.

Jessica Gordon-Burroughs

[This text is an adapted fragment of the article originally published as: Jessica Gordon-Burroughs “Looking Back and Away: Jaime Barrios’s Film Club (1968)” Discourse, 42.3 (Fall 2020): 281-304.]

Source: Interview by Jessica Gordon-Burroughs with student filmmaker Tony Joseph, director of Superbug. October 21, 2022. Photos of Tony Joseph c. 1973 by photographer Alfonso Barrios (1936-2023). Photos courtesy of Mary Harrison. Video by Michael Jacobsohn.