For some years now, the archival turn has entered the roster of “turns”—corporeal, affective, materialist, neo-materialist, environmental …--that from time to time realign contemporary art and thought. Just like those other turns, the archival turn obeys many different causes. In part it is one of the consequences of the culture of information overload and immediate access we now live in. The digital revolution has brought endless databases and image banks within reach of anyone with online connection—which is probably just about anyone—making the documents of the past easily accessible but also downloadable, modifiable and combinable in virtually endless permutations. In addition, the technologies that give us access to these repositories also enable the automatic recording and constant storage of everyday life. As a result, the transformation of experience into document is now almost instantaneous, and life has increasingly become a continuous addition to our personal archive (I live, therefore I document), or even, in a more pessimistic view, an occasion to expand our digital footprint in social media. The archival shift is also the result of the popularity of memory-related industries: fiction films, TV series, documentaries, docu-series, virtual recreations, museums, theme parks, memorials, and anniversaries all traffic in images of the past. These media are sources of information but also forms of entertainment and spectacle thanks to their immersive nature and the sensual experience they provide.

For minority communities, the drive to record and archive is a political necessity that long precedes the popularisation of the internet and the rise of a digital media ecology. For the queer community, for example, made up of a diverse spectrum of heterodoxies of gender, sexuality, and social alignment, the visibilisation and vindication of sexual freedom have always been allied to a deep commitment to salvaging and preserving a past that has been systematically erased or trivialised by the institutions that safeguard official memory. The early years of gay-lesbian militancy in the United States, for instance, gave rise to the founding, by a collective led by Joan Nestle, of The Lesbian Herstory Archives in Brooklyn, as well as the publication by historian Jonathan Ned Katz of Gay American History (1976), a compilation that documents sexual heterodoxy in the United States since colonial times. Other archives created subsequently in different parts of the world (IHLIA in Amsterdam, ONE Archive in Los Angeles, Schwules Museum in Berlin, Skeivt Arkiv in Bergen, and the extraordinary Archivo de la Memoria Trans in Argentina, to name but a few) also arise from an activist drive that believes that queer dissidence is also archival dissidence, and that being a political subject presupposes a critical orientation towards the present and the future but also towards the past. The awareness of the past gives a historical dimension to the experience of the present and helps to collectivise individual dissidence, inserting it in a timeline that includes the echoes of other lives and forms of resistance. Moreover, minority memory is an indispensable tool for deactivating and nuancing the (often monolithic) narratives of official history. The archive can then be a privileged site for articulating subversive counter-memories that re-evaluate the past in order to expand the possibilities of the present and the future.

The subversive potential of the queer archive stems largely from its contents: from the way it documents the everyday, the ordinary, and the personal. In this respect, queer archives are a counterpart to the official archives created by the institutions in power. In these, gays, lesbians, transsexuals and heterodox individuals of all stripes appear in medical records and police reports as aberrations, sick people or criminals who must be corrected, isolated, classified or punished. Conversely the queer archive, created from the ground up by and for the dissident community, tends to compile the everyday details of parties, affects, journeys, fleeting pleasures and personal relations, experiences which often leave traces in precarious materials that have no place in official archives. The Museum of Transology (housed at the Bishopsgate Institute, London), IHLIA and The Lesbian Herstory Archive, for example, include clothing and idiosyncratic personal objects in their collections, usually accompanied by the stories of their former users.

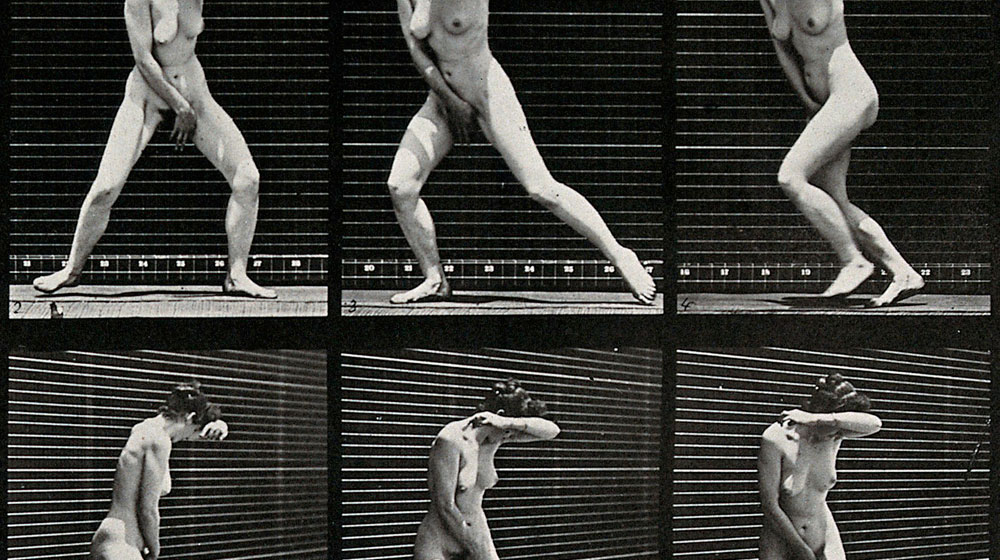

Queer everyday life is also recorded in photographs and films. The emergence of modern queerness, which Michel Foucault dates back to the late 19th century, coincides with the popularisation of new visual media: with the emergence of cinema as a public spectacle and with the appearance of hand-held cameras equipped with rolls of celluloid film, which required less exposure time than previous photographic supports, were easily affordable, and were avidly consumed by broad sections of the bourgeoisie. As Tom Waugh documents in Hard to Imagine (1996), an exhaustive study of gay film and photography prior to the sexual liberation movements of the late sixties, both media endowed the incipient queer communities of Western metropolises with a visual archive. This archive abounds with erotic images, both recorded for personal consumption and also for commercial distribution, as well as everyday moments experienced with families and friends. The archives of the Kinsey Institute, founded by Alfred Kinsey at Indiana University in 1947, contain what is perhaps the largest collection of such audiovisual material, particularly from the late 19th century to the first few years after World War II. Filmmaker Kenneth Anger, a personal friend of Kinsey's, worked assiduously with the Institute on locating materials and brokering their acquisition, an activity reminiscent of his role as archivist of Hollywood scandal in the Hollywood Babylon book series. Most of the Kinsey Institute's visual collection, as well as similar collections, consists of orphan film and photography: images that come to us without context or clear authorship, or made by amateurs whose names are barely known—fragments that often pose problems of dating and legibility. Whether erotic or domestic in nature, these images are often stereotyped and aesthetically flat, of value particularly for those who made them or appear in them. For the rest of us, however, they bear witness to an anonymous, hidden and often joyful resistance, and provide us with a visual and material memory unrelated to persecution, pathology, control, diagnosis, or correction.

In addition to pornography and amateur cinema, avant-garde film is the third great archive of the queer image. It is an involuntary, intermittent archive, scattered throughout the numerous repositories of experimental film. Although it wasn’t created in order to bear witness to sexual insubordination, it was nevertheless close to it from the start. Some early examples are the transvestism in Un chien andalou (1928) and Entr'acte (1924) and the homoeroticism of Salomé (1922) and Lot in Sodom (1933). In contrast to the aesthetic innocence of amateur or home movies, the avant-garde is stylistically self-conscious, linked to different artistic movements, and marked by the personality of its authors. But it nevertheless shares some features with anonymous and amateur film. Its authors often reject the professionalism and high production values of commercial cinema and embrace spontaneity and improvisation, just like home movies do. Moreover, experimental film has a communal, cooperative nature; family, friends and lovers are involved as cast and technical support, so that many experimental productions are, in part, home movies of sorts—family albums documenting intimate, marginal artistic scenes. This is the case of the early productions of Werner Schroeter, the Barbés-Rochechou-Art group, Andy Warhol's Factory, the Els 5 QK's collective in Barcelona in the 1970s and 80s and the British New Romantics of the early 1980s.

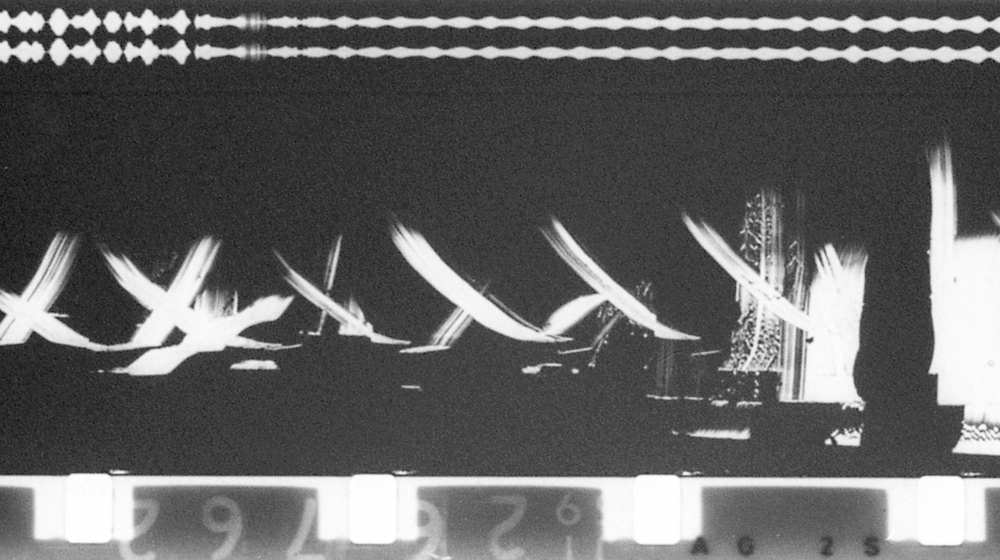

As a site of dissident counter-memory, the queer archive differs sharply from the official archive. The etymology of archive links the notion of origin (arché) with that of governor, ruler (archon), or exclusive interpreter of the law. It has often been repeated that the archive is the seat of power, law, and social order; that it guarantees authority and historical continuity. At the same time, in Jacques Derrida's famous interpretation, it is also besieged by rupture, dispersion and loss, and full of indeterminacies and leaks. It’s "an origin without concept", split and multiplied by its own heterogeneity, by the accumulation of the materials that comprise it. The queer archive has a greater affinity with these cracks and elisions than with the traditional archive's aspiration to order and continuity. As argued by Daniel Marshall, Kevin Murphy and Zeb Tortorici, among others, queer subjects cannot have a conventional history, in part because their archives are elusive and dynamic. These archives are full of gaps and uncertainties, of unassimilable excesses and illegible remnants. There can be no order in an archive created from erasure and exclusion, no continuity in a denied history, no transparency in what has been the secret par excellence in Western bourgeois societies: sexuality. For its part, queer sexuality is the secret’s secret, so its documented history is much more tenuous and must be inferred from fragments, silences and ruins.

This oscillation between loss and excess, between what is missing and what is illegible or irreducible to some form of historical coherence, makes the queer film archive, in all its facets, more a space for speculation than a seat of authority; its documentary or evidential value carries less weight than its use value and its potential for activation. But how can we activate erasure? How can we use excess?

The spectre of what has disappeared hovers over the audiovisual archive, the uncertain shadow of what we have lost but without, in many cases, knowing exactly what it consisted of because its existence was never recorded: countless personal narrow gauge films that ended up in the trash or were seized and destroyed. Thanks to some of these being rescued, we have recovered snippets of history. The video LSD: Retroalimentación (1998), by the lesbian-queer collective LSD, inserts family photos and film of the poet, feminist, and militant anarchist Lucía Sánchez Saornil, who was a relatively open lesbian during the years of Spain’s Republic, in a rapid chronicle of queer activism in the nineties, edited like a video clip over a background of electronic music. In this way they make the half-forgotten poet relevant in the present and provide contemporary queer activism with a godmother who connects them, in turn, with a history of anti-Francoist resistance. Peter Toro, audiovisual producer and archivist, is rescuing footage of the first gay pride demonstrations in Madrid shot by amateur super-8 filmmakers and by news agency camera operators. Other losses, never retrieved, have specific names and dates: Bill Vehr's film Brothel, seized at the US customs after a screening in Canada and never recovered; Kenneth Anger's early films, up to five titles, presumably lost, and another one destroyed by a laboratory; the lost films by José Rodríguez Soltero, listed in a filmography deposited in The Film-Makers' Cooperative, to which should also be added the videos he made in the 1970s with the Young Lords, in New York; the super-8’s seized from Iván Zulueta in a police raid and never returned. Alongside these are the unfinished projects: the films of José Antonio Maenza, which survive as rough cuts, mere memories of a work he was never able to complete.

In view of such gaps in the archive, it is worth fabulating a speculative history that resists loss. Otherwise, says Saidiya Hartman, we must resign ourselves to the corrosive effect of hostility and indifference. Against them, Barbara Hammer conceived her historical projects Nitrate Kisses (1992) and History Lessons (2000), built on the ruins of a devastated past. Cheryl Dunye goes even further: The Watermelon Woman (1996) imagines the fictional biography of Fae Richards, a lesbian Hollywood actress of African descent for whom she invents a whole archival apparatus: interviews, photographs (by Zoe Leonard), and newspaper clippings. Although the Richards of the film did not actually exist, surely there were similar figures who did. Although it may not be possible to salvage specific historical figures, devoured by the homophobia and systemic racism that have consigned their lives to oblivion, it’s nevertheless possible to recoup, at least, the possibility of their existence. There’s a history of things without history.

As well as serving as a testimony to loss, the archive is also a collection of excesses that defy insertion within any temporal narrative or conceptual category. Images always have an irreducible aspect that defies containment—a surplus that Jean-François Lyotard named “the figural” and Roland Barthes punctum; both concepts are linked to the representation of the body and its attendant affects. Even an archive of sexual dissidence (by definition an archive of the uncontainable) has moments that stand out as unassimilable remnants. What to do, for example, with the shadows of occultism in the queer image: in Harry Smith, Kenneth Anger, Derek Jarman, not to mention trans activists like Angela Douglas, a fervent believer in extraterrestrial contact? How does this fit with the queer politics of the present? With the histories of past resistance?

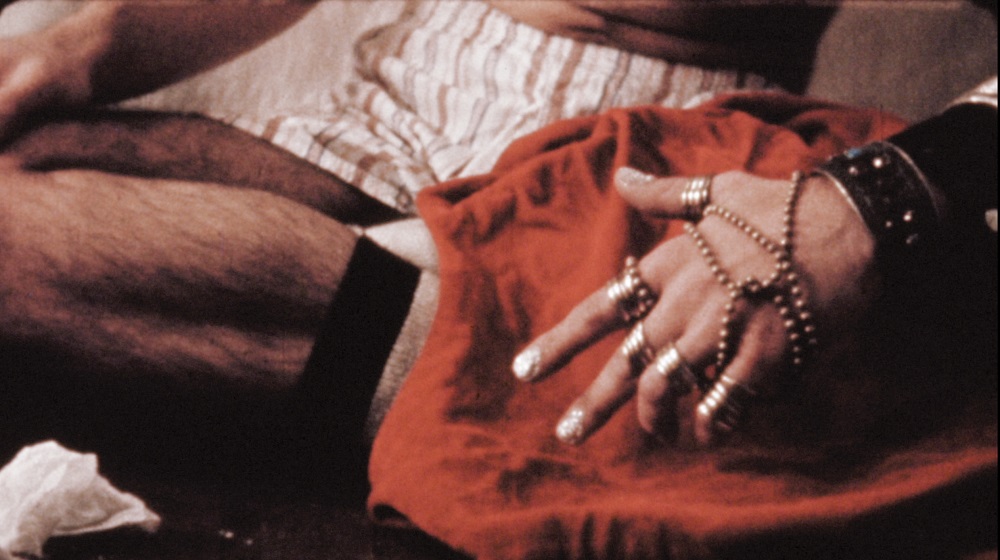

At other times excess is more discreet, emanating from the indexical nature of the filmic image. A gesture, a face, an article of clothing or haircut that take us to another era are traces of fleeting moments that remain in the photochemical image and reflect the singularity of bodies in their passage through time. Several projects by William E. Jones remix the porn of the 1970s and 80s, the golden age of celluloid pornography, just before the industry's conversion to video. They recover the moments before or after a sexual encounter, which they take out of the image and, in a way, out of history. The remixed fragments situate these films in an antiquated material culture, in geographical settings that have changed radically (the San Francisco or New York of the 1970s and 1980s) and in a media ecology of the cassettes and vinyl records playing during sex, TVs that are sometimes left on in the background of the image, and posters advertising the films and stars of the day. Archival excess is the other side of erasure. It can provoke nostalgia or memory, refer to constellations of taste that shaped an era or be the starting point for stories tangential to the narratives of liberation. Without necessarily connecting with these narratives, they accompany them, give them a particular density and make them converge with other histories and discourses that show sexuality as a centrifugal force that also affects numerous bodily and material adjacencies lying beyond the vicissitudes of the sexual encounter. The history of sexuality is many histories at once.

Despite being built up in the shadow of loss, the queer archive opens up the possibility of a reparative, compensatory and also critical relationship with the past. Engagement with the archive stems from an awareness of its incompleteness but also from a refusal to accept these limits. Through their work, filmmakers, artists, collectors and archivists suggest that history is an open-ended process. It can be experienced at least twice. Experienced in the first instance as tragedy, it can be revisited as comedy in the sense given to the term by the venerable, not at all queer critic Northrop Frye: as an allegory for regeneration and for the continuity of life. In this case, it’s a deferred life, refracted by the materials of the past that can be recovered and replayed a second time with an emancipatory vocation that, without falling into naïve optimism, rejects catastrophe and oblivion as the only possible horizons of experience.

Juan Antonio Suárez