Stacey Steers has grouped together this programme's three films, as well as some of the resulting installations, under the name of Night Reels. This name refers to different characteristics in terms of their aesthetics; firstly, the material nature of film (evoked by the word reel, i.e. a roll or can of analogue film), secondly, the universe of the early years of cinema (when films were defined and organised based on the number of reels they filled), and finally, the night as both a mental and physical state that's open to fantasy, memory and introspection. All the films in the trilogy can be positioned along these lines, using one particular creative device and also recurring themes.

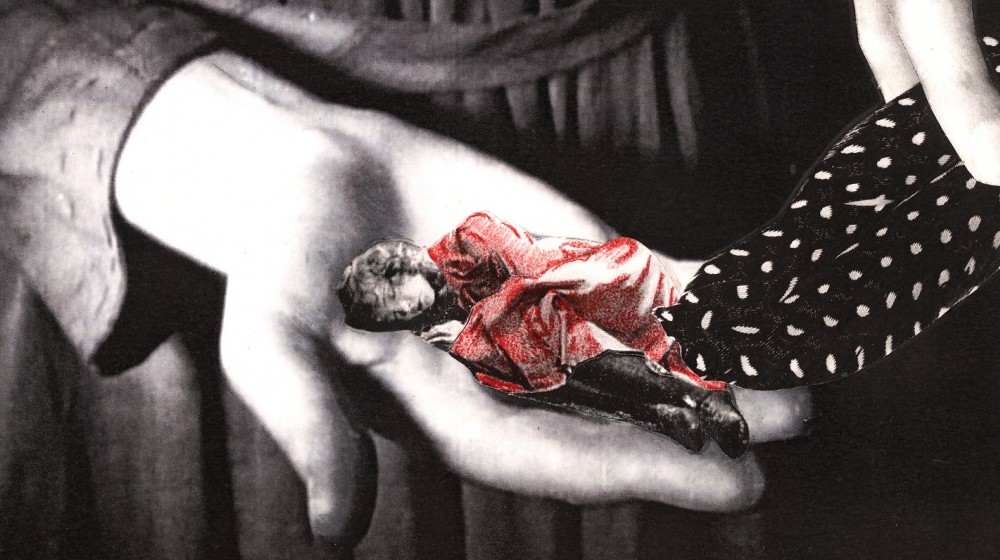

One common feature in experimental cinema is that cineastes create their own way of working; even more so in the field of experimental animation, where producing a film image by image is the initial condition of every idea (perhaps an extreme case in point would be that of Parker and Alexeïeff's pinscreen animation). In this trilogy, Steers explores collage as a technique to construct images, combining 19th-century prints and illustrations with fragments from silent films printed on paper. The cinematographed faces of actresses such as Lilian Gish and Mary Pickford are carefully cut out, frame by frame, then combined with another graphic universe (in Phantom Canyon the "cinematographic" image would correspond to Muybridge's photographed sequences; i.e. to the historical link between both universes). In this way, the filmed image, usually dematerialised, becomes physical, thereby achieving the tactile goal that drives part of experimental cinema, in both practical and creative terms. In this respect, it's interesting to note that the first thing we see in Phantom Canyon is a pair of hands and then scissors, while the characters in the other two films carry out a range of manual actions. There's also a beautiful shot in Night Hunter when the character rests on the palm of a hand.

It could be said that Steers uses collage more as a technique to create images than as animation. When talking about her work, she explains that, in general, each image is constructed individually and then photographed as a sequence, frame by frame. But while these films clearly come from the tradition of collage or cut-out animation, they also exist in their own right, with their own beat that differs from some aspects of this tradition. There's no fast or jerky pace (as there might be with Vanderbeek) but a smooth continuity of movement in a universe made up of fragments. Nor do they explore the technique of high frequency substitution used by some experimental cut-out animation (such as the films by Caroline and Frank Mouris). Instead, they resort to a slight vibration of surfaces. Two characteristics that surely form part of those aspects that are essential to achieve the hugely evocative power emanating from these films.

How the cineaste works may be a constant in this trilogy but so are various thematic motifs. The three films depict a universe inhabited by female protagonists who seem to live in seclusion, in interior spaces, sometimes stalked by creatures (a male character in Phantom Canyon, a snake and insects in Night Hunter), going through situations of transformation or transition that may evoke motherhood (explicitly in Phantom Canyon and more metaphorically in Night Hunter), relationships or even artistic creation itself (in Edge of Alchemy). There are recurring motifs in this universe, such as the presence of insects and also hybrids, both human-animal (the bird woman in Night Hunter) and human-plant (the creature in Edge of Alchemy), as well as animated motifs such as leaves growing from eggs or a hand (in a fascinating shot in Edge of Alchemy). It's these representations and their internal logic that make us feel we're witnessing someone's own imagination; like an evocation of the past or future filtered by fantasy, like the process of creating a dream or crystalising an experience by means of a fantasy world.

The creative device and themes reinforce each other throughout the trilogy. The frame-by-frame animation and Steer's chosen technique of carefully constructing each image means that each film takes years to produce; it's obsessive work that reinforces the very situation of the films' protagonists. It could also be said that the collage technique is reminiscent of thought processes, of layers of memory or imagination, insofar as it overlays and combines different layers - and this is specifically how it's used by Steers.

In Edge of Alchemy there's a motif that's distinct from the other films: a set of laboratory instruments (nevertheless possibly reminiscent of the domestic instruments in Night Hunter). Among these instruments is a magnifying glass, appearing on more than one occasion throughout the film. Sometimes it enlarges the image behind it (magnifying Pickford's face even more), but normally it serves as a means to access another world, another layer behind the surface. Stacey Steers' films are this magnifying glass. To watch them is to hold the magnifying glass in your hands and realise that it's also a mirror.

Daniel Pitarch (Colectivo Estampa)