The technique

In May of 1965 Andy Warhol, by then one of the most successful artists in the world, confirmed that he had stopped painting the year before to dedicate his entire time to cinema, because “films are more exciting”. However, films are also harder to sell: there’s no “original” film print that makes money for museums or collections, and the type of cinema that Warhol tackled right from the start was way off the necessary commercial requirement to be financially profitable.

This decision to give up painting, even if it was on a partial and temporary basis, was Warhol’s first great political action. To forsake million-dollar sales of paintings such as Marilyn and the Liz portraits to make films like Sleep and Empire, breaking all commercial moulds, not only vindicated his non-commercial approach as a filmmaker but also confirmed the seriousness of his film company.

Between 1963, when he made Sleep, and 1968 when he directed his last film, Blue Movie, Warhol filmed hundreds of films. For the most part, there was no post-production process: the film was completed once the reel was shot, whether it comprised of 100 or 1,200 feet, had sound or not, was projected at 24 or 16 frames per second, was in colour or black and white. It was the reel, lasting 3, 4, 33 or 48 minutes, that became a minimalist articulatory in Warhol’s cinema, and the only editing work carried out was the splicing of one reel after another until he had the right duration that he wanted. By subordinating the content of the image to this fixed structure, Warhol was hailed as the godfather of structural/materialist film, championing duration as a specific dimension.

Warhol’s cinematographic art wasn’t that different to his painting method: he used the same content (pop elements of American society that were either objects, well-known personalities, political figures or wartime events, filtered by their own media imprint). There was still the same serial structure, random approach to composition on a film’s different panels (or reels), the same transition between black and white and colour, the same mechanical and impersonal technique when carrying out the work (printing, camera)… It was the component in his films, the element of a specific and physical duration, which ended up putting off his audience and the market.

Warhol’s film production was so vast that to this day we still can’t grasp the global image of his work. The fact that his films were finished and ready to be projected once they were returned from the lab (the 16mm Auricon camera that Warhol used taped the sound directly onto the actual film, meaning that there was no need to insert sound at a later point) doesn’t allow us to dismiss the outlines or rejects on the many reels which are now being recovered from his . Nor can we confirm their unedited nature as, with Warhol revolutionising cinema, he also radically changed their method of screen. It’s probable that many of the films that we may have considered to be uneditable could have been projected in private spaces like the Factory or as the backdrop to performances of The Velvet Underground and Nico.

There were two aesthetic tendencies in Warhol’s cinema that often overlapped. On the one hand, there was the deadpan view from the fixed camera in his early works. And then, there was the way Warhol got carried away with the mechanism of the camera and started exploring each and every one of its possibilities. Here was the restless view of a filmmaker, shifting his camera from one point to another with zooms and great dizzying sweeps, experimenting with the aperture by filling it with blinding light or darkening an image, moving his characters in and out of focus… And, on so many occasions, indicating a clear example of attention deficit, he lost interest in the dialogue conducted in front of the camera to immerse himself in empty walls.

It was within this tireless manipulation that Warhol started to play around with camera editing and discovered stroboscopic cuts. Apart from his use of the reel as an articulatory unit, which would have a huge aesthetic impact within structural cinema, Warhol’s other major contribution to cinematographic art was the use of stroboscopic cuts. This consists of turning the camera on and off between one take and the next which, with an Auricon, causes a click and flash during the editing in order to identify the take changes. However, Warhol converted this element from what was essentially a technical resource into an aesthetic one, just as he maintained the queues (with numbering and specific information for the projection room) for their artistic value, as an assembly between the reels.

The political aspect

The Nude Restaurant isn’t Warhol’s only politically-inspired film, but it was certainly the most militant one. Warhol claimed that The Nude Restaurant, like Blue Movie, was an anti-war film, but actually it was more than that. It was the portrait of an era, a reflection of North American counter-culture. The serious tone of Viva while discussing Cuba, and of Julian Burroughs on the resistance movement, take the film a step beyond aesthetic provocation.

Warhol’s cinema is deeply humanist. Unlike previous structural film, in which the human figure was normally missing, Warhol always focused on human presence, on the portrayal to the narrative, the image to voices, beauty to intelligence. Warhol’s cinema is “too human”: beyond a formal exercise, his characters reflect terror, alienation, political and individual claims, loneliness and love; they relate with Beckett by means of the absurd, the vulgarity of personal relationships referring to Sartre (“hell is other people”) and the constant isolation makes us think of Antonioni. All his work, on the back of a combination of the most radical experimentalism and independent narratives, constitutes a broad portrait series of American society in the sixties.

Politics and sex, organized militancy and individualism: both concepts merge in the hippie figure. A hippie, from a para-anarchist position, revindicates their personal freedom while forming part of a collective; they fight for free love at the same time as protesting against war. Personal and collective militancy are confused. There’s room for life in its multiple dimensions, ranging from the activist Julian Burroughs to the seemingly apolitical Taylor Mead, who fights daily for our right to sexual expression and is persecuted all the time because of this. In the same way, Andy Warhol’s apparent apoliticism has also been greatly criticised, plus his complicity with the affluent. However, we mustn’t forget his personal activism (described by his biographer Victor Bockris as an “icon of gay liberation”), and how it is reflected in his art.

What The Nude Restaurant achieved was to seamlessly synthetise sex and politics, Freud and Marx. In Blue Movie Viva knows just how to express this confluence between personal and political protest in a poetic way when he says to Louis Waldon: “I don’t know whether it’s your political ideas or the sun that’s making me randy.” The sex in Blue Movie is, according to Vincent Canby, “a supreme act of political protest”.

The Vietnam war also featured in “Hanoi Hannah”, one of the Chelsea Girls episodes based on the playwright Ronald Tavel’s script, which was originally going to be called “Vinyl”. The original title and the fact that the characters repeat the name convert “Hanoi Hannah” into a follow-on from Vinyl, which was at the same time an adaptation of Anthony Burgess’ highly political novel Clockwork Orange. “Hanoi Hannah” is, together with The Nude Restaurant and Juanita Castro, one of the few examples of a politically-inspired film of Warhol’s.

The Life of Juanita Castro addresses the US media view of the Cuban revolution in a farcical manner. The film starts off with an article written by Fidel’s sister called “My Brother is a Tyrant and He Must Go”, and then becomes a humorous political satire of both the revolution and Juanita herself, who ends up collaborating with the CIA in an effort to depose her brother. The human and familiar element of this political confrontation is undoubtedly what Warhol liked about it, and he even invited an ex brother-in-law of Fidel’s to appear in the movie as a draft dodger. What is also significant is the inflammatory choice of women to play the roles of Raúl and Fidel Castro and Che Guevara.

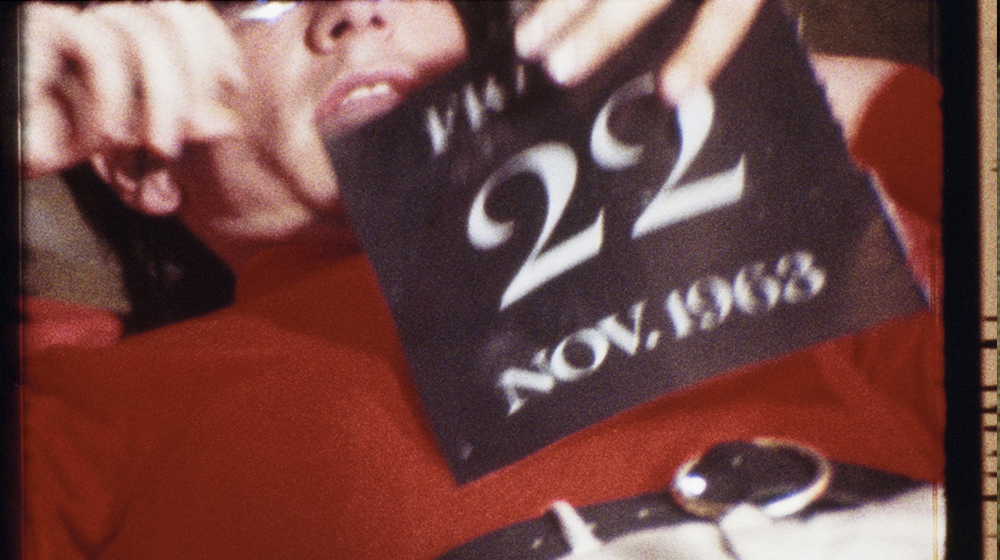

Another huge political event from that period was the assassination of Kennedy, which was reinterpreted by Warhol in his film Since in a funny and also mostly improvised fashion. However, once again, Warhol wasn’t so much interested in the actual event, but rather in the social and media impact that it had. He was fed up with the radio and television priming viewers for lasting sadness, and created Since as a response to this media manipulation. Since was therefore not the recreation of the president’s assassination, but a harsh criticism of what had actually become pure prime-time television.

Under the guise of pop (political figures, significant events, wars made trivial by consumer elements and spectacle, on the same level as his famous dollar bill or the soup can), Warhol’s art on both canvas and film may become a scathing and accurate political weapon through parody and ridicule. And it is always human, too human.

Alberte Pagán